GOLDEN LADS AND LASSES: "Shakespeare for Children"

Abstract

The Folger Shakespeare Library's current (2006) exhibition, "Golden Lads and Lasses": Shakespeare for Children, explores the many ways in which Shakespeare's stories have been adapted, modernized, and packaged for children. The array of materials in the show — Victorian storybooks, paperdolls, comic books, and movies — provides an inspiring illustration of Shakespeare's continuing appeal for younger audiences.The Folger's latest foray into its vast collection of Shakespeariana has resulted in a fascinating look at the many ways Shakespeare's plays and plots have been adapted for children. Arranged chronologically, the exhibition begins with the impossibly small Elizabethan hornbooks used by schoolchildren and ranges up through the past decade's rush of films renovating Shakespeare for teen audiences, including Ten Things I Hate About You (1999), a hip rethinking of Taming of the Shrew, and Romeo + Juliet (1996), the remarkably successful Baz Luhrmann film featuring Claire Danes and Leonardo DiCaprio as the doomed lovers.

|

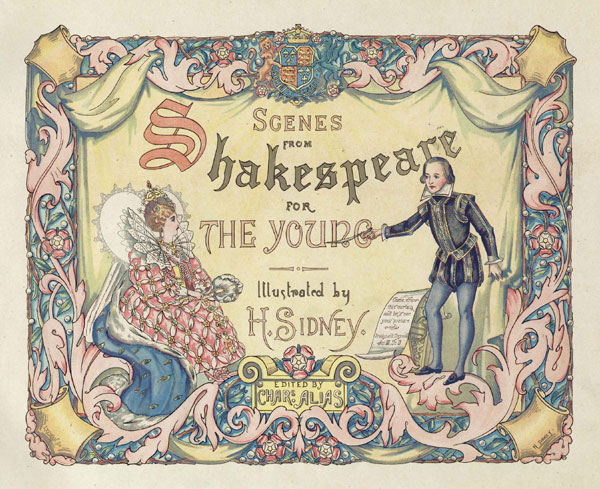

Between these two extremes, the Folger presents a dizzying range of materials designed for children, mostly from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Charles and Mary Lamb's famous Tales from Shakespear (1807) may be found here in dozens of editions, most featuring dazzling, hand-coloured illustrations. The nineteenth century was a ripe time for children's books, and the exhibition includes a wonderful breadth of examples, ranging from Edith Nesbit's Children's Stories from Shakespeare (1901) to Fay Adams Britton's blends of fairy tales with Shakespeare (1896), to Skelt's Juvenile Drama adaptations of Othello (c. 1840). Each of the beautifully illustrated books appears almost in miniature, the better to fit into tiny hands. The attention to detail and design in these print editions will fascinate readers and scholars of material culture alike.

The inclusion of Henrietta and Thomas Bowdler's heavily edited Shakespeare (1807), the basis for generations of schoolchildren's editions, helps to illustrate how Shakespeare began to be explicitly tailored to serve as a moral compass for the Victorian period. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the editions for children. Moralized retellings of Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, and Merchant of Venice assure their readers that Shakespeare's plays serve as "instructions for our conduct in life." Modern books are less heavy-handed and generally seek to delight young readers with lively reworkings of the plays rather than to instruct them. Lois Burdett's Macbeth for Kids (1996) introduces children to the Scottish play with an abbreviated plot set in rhyming couplets, and Tina Packer's Tales from Shakespeare (2004) combines famous lines from the plays ("Is this a dagger I see before me?") with simple storylines.

Of particular interest to the exhibition's curators are the Shakespearean adaptations that focus on women. Beginning with a small book called Judith Shakespeare, by William Black (1884), the exhibition illustrates how retellings of Shakespeare's biography and plays were marketed to girls. An article in a magazine for girls from 1887, "Shakespeare as the Girl's Friend," exhorts young women to look for role models in Shakespeare's female characters as it teaches them how to understand the plays. More recent novels use the plays as a place to launch their own independent explorations into the interior lives of Shakespeare's women. Books such as Dating Hamlet: Ophelia's Story, by Lisa Fiedler (2002), and Shylock's Daughter, by Mirjam Pressler (2002), follow a recent trend in fiction by refocusing stories on the "secondary characters." (Think of Gregory Maguire's Wicked (1995) or Sena Jeter Naslund's Ahab's Wife (1999), which tell the stories of the Wicked Witch of the West and the lonely wife of the Pequod's captain.) The urge to open these books and see for oneself how these authors have chosen to retell Ophelia's story can be nearly overwhelming. As an advertisement for the bookstore, this exhibition is a victory!

One of the most intriguing recent genres featured in the exhibition is the comic book or graphic novel. With origins in nineteenth-century picture books, the Shakespearean comic book found a niche in the middle of the twentieth century — the exhibition features half a dozen gorgeous editions of Hamlet and Macbeth from the period — and has since evolved into a postmodern extravaganza in the hands of contemporary artists. Marcia Williams's graphic novel for A Midsummer Night's Dream (1998), easily the most popular play adapted for children, stands as one of the show's highlights. She employs Elizabethan English for the play's dialogue within the frames of the comic, but then includes the "responses" of the audience, who are drawn around the margins of the page. The hecklers' places on the page correspond to their status, as either standing penny-payers or moneyed elites. As one wry groundling tells his friend while he gazes up at Helena, "Wish my wife was obedient as a spaniel!" The result of this bold graphic design is a delightful representation of the theatrical experience.

Interspersed between the more formal museum cases are paintings and drawings by local schoolchildren. Portraits of Shakespeare and designs of plays by elementary students hang proudly next to the First Folio that remains on display in the Folger's Great Hall. Hilarious letters written by students "in character" are worth their own visit. (Lady Macbeth assures her husband in one note that she is "icksploding" with ambition.) This attention to the experience of younger visitors is carried through in a case filled with Shakespeare-inspired toys, which includes the Hamlet finger puppets and the Shakespeare dolls that grace many a teacher's desk. The exhibition signage and wall text appears to be similarly aimed at younger visitors, but the result unfortunately serves neither child nor adult. Apart from a few gems that children might find intriguing — the fact that early modern theatergoers ate nuts, not popcorn, intrigued one tourist on my visit — at times the exhibition texts can be opaque, or even condescending to young readers. Creating a show with archival materials that will appeal to young, sophisticated visitors is no easy feat, however, and the show's impressive content makes the signage problem practically unnoticeable.

Wandering through the exhibition led my companions to recall their own first experiences with Shakespeare. While one had been taken to see a play, another had treasured the Lamb stories, and yet another had been read the plays as a very young girl. Discussion turned to the quality of the newest adaptations in the exhibition, particularly films such as Disney's Baby Einstein: Baby Shakespeare World of Poetry (2002) or Mike O'Neal's Green Eggs and Hamlet (1995), and whether experiencing Shakespeare through these films is the "best way." Given the potential of online editions of Shakespeare, which can feature every performance adaptation on film and dozens of images from manuscript, print, and the fine arts, there are now thousands of ways for a young person to access the Bard. One need only look at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Shakespeare Project, including Hamlet on the Ramparts, to see the possibilities for online editions for children. This virtual abundance makes the carefully hand-coloured illustrations of the nineteenth century seem quaint by comparison, but one hopes that we can come close to providing something as beautiful for our own children.

Although Shakespeare's stage did not admit young women as actresses, Shakespeare's boy actors impersonated a dynamic set of girl characters, including the thirteen year-old Juliet, fourteen year-old Marina, fifteen year-old Miranda, and sixteen year-old Perdita, and other characters, girls such as the wily Bianca, the tragic Lavinia, the canny Anne Page, and the iconic Ophelia, whose ages are not specified, although all of them are called "girl," usually by their fathers. Over the course of his career, Shakespeare's attention to girls and girlhood is, arguably, one of his ongoing preoccupations: the term "girl" appears sixty-eight times throughout his work. "Girl" can be used to label independent or recalcitrant behavior (as in Capulet's description of Juliet as a "wayward girl"), to highlight tragedy or victimhood (as in Lavinia's epithet, "sweet girl"), as well as innocence (as Leontes recalls "in those unfledged days was my wife a girl"). Shakespeare's ideas about girlhood, then, are neither confined to stereotypes of demure submissiveness nor limited to promiscuous service; rather, Shakespeare's girls claim their right to self-determination in the face of parental opposition, vigorously defend themselves and their families, and express their feelings and their fears with wit and verve. As Caroline Bicks points out in her contribution to this volume, "girl" is often used to signify the space between puberty and marriage, and it is this particular time "that enables unique acts of female creativity," as girls act to escape or challenge the roles that are assigned to them and can imagine and perform a variety of other options.

Shakespeare's vivid characterizations of girlhood thus inspire some of the most famous adaptations and appropriations of his work. Mary Cowden Clarke's The Girlhood of Shakespeare's Heroines(1851), a set of fictional prequels that conjure the girlhoods of Shakespearean characters for the girl reader, with the idea of contributing to the status of Shakespeare as a "helping friend," offering "vital precepts and models" of femininity "to the young girl." Cowden Clarke traced her interest to another adaptation, Charles and Mary Lamb's Tales from Shakespeare (1807), which offered versions of Shakespeare's plays specifically "for young ladies," explaining that girls had more restricted access to their fathers' libraries than boys, and enjoining boys to explain the difficult parts to their sisters. Their versions of Shakespeare were tailored, therefore, to their ideas about the sensibilities and limitations of the girl reader. For Cowden Clarke, by contrast, her imaginative attentiveness to the prehistories of Shakespearean girl characters reflect her own ideas about the interest and importance of girls' lives and experiences.

Long before Cowden Clarke and the Lambs, however, some of the very earliest adaptations of Shakespeare focus on girls and girlhood. The Tempest, or the Enchanted Island (1670), an adaptation of The Tempest by William Davenant and John Dryden, takes a play with only one girl character, Miranda, and gives her a sister, Dorinda; Ariel, the spirit who takes on many female parts in Shakespeare's The Tempest, was played by a girl actress, and he is given a girlfriend, Milcha. Dorinda's boyfriend, Hippolito, was also a trouser role. As a kind of tacit celebration of the arrival of the actress on the public stage, the play is suddenly filled with girls. The process of adapting Shakespeare often has girlhood at its very heart: a Restoration adaptation of Shakespeare's Pericles, George Lillo's Marina (1738) focuses on Marina's story, as it is depicted in the final two acts of the play, sidelining the peregrinations of patient Pericles to the triumph of her virtue and virginity. Film adaptations of Shakespeare, such as Ten Things I Hate About You and Baz Lurhmann's William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet, brilliantly frame Shakespeare for the consumption of teenaged girl audiences, while the visual arts are consistently drawn to Shakespeare's girl heroines, from the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery to Gregory Crewdson's recreation of John Everett Millais's iconic Ophelia.

Shakespeare's own involvement in the processes of appropriation and adaptation also leads him to expand upon girl characters and promote girlhood. For example, The Two Noble Kinsmen, an adaptation of Chaucer's Knight's Tale, elaborates Chaucer's character of Emily, moving far beyond Chaucer's own expansion of the character from his source material in Boccaccio's Teseida. Shakespeare endows his Emilia with a rich Amazonian history, including her girlfriend, Flavina. With the Jailer's Daughter, an adaptation of Ophelia, mad for love, Shakespeare embellishes his own source material, and each of the Jailer's Daughter's soliloquies, charting the progressive loss of her wits, is longer than the last. Alongside Shakespeare's creation of these major girl heroines, Two Noble Kinsmen opens with a procession of widows, who, no longer girls themselves, nevertheless frame the play's attention to the trials of girlhood within the larger scope of women's experiences, including those of the stalwart Hippolyta. Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet adapts Ovid's Pyramus and Thisbe via a set of continental rewritings including Masuccio Salernitano's Il Novellino (1476), Luigi da Porto's Giulietta e Romeo (1530), Matteo Bandello's Giulietta e Romeo (1554), Pierre Boiastuau's Histoires Tragiques (1559), as well as, in England, Arthur Brooke's The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet (1562) and William Painter's Palace of Pleasure (1567). It foregrounds Juliet's girlhood, adding precise details of her age, and developing her as a character of exquisite intelligence and powerful drive. Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, of course, inspired one of the earliest adaptations of Shakespeare by William Davenant (1662), a key event in the history of women on the English stage, and the beginning of a long history of adaptations of the play that place girlhood at the forefront, from Thomas Otway's curious fusion of Juliet and Lavinia in The History and Fall of Caius Marius (1680) to the theatrical experiences of Viola de Lesseps in Shakespeare in Love (1999).

Girls thus enjoy a special place in the history of Shakespeare adaptation. And there is, in fact, a special kind of kinship between girlhood and adaptation. Adaptation has often been considered secondary, or a derivative of the original masterwork, just as women were traditionally positioned as the "second sex," with their derivative beginnings in Adam's rib. Yet as adaptations provide an opportunity for a broader set of voices to weigh in on the canonical original, including girls, they also develop a relationship to their source material that may be understood in terms of a playfulness, from witty and satirical to energetically creative: qualities that also evoke ideals of spirited girlhood.

This special issue of Borrowers and Lenders explores the relationships between Shakespeare, Adaptation, and Girlhood. The first group of articles, under the subheading "Screen," examines adaptations of Shakespeare for television, YouTube, and film, with each medium representing girlhood in different ways. Ariane Balizet's discussion of girls' references to, anxieties about, and relationships with Shakespeare on the small screen focuses less on the adaptation of Shakespearean plots or characters for television than on the idea of Shakespeare himself as a representative of high culture and patriarchal authority, usually in a classroom setting, casting the girls as subordinate to it. However, her examples reveal girl characters in shows from My So-Called Life to Orange is the New Black prevailing and even triumphing over Shakespearean content, reversing the expectations of inferiority and transforming Shakespeare instead, as Balizet puts it, into a "tool against marginalization."

In the context of the emphatically democratic YouTube, in Stephen O'Neill's contribution, Shakespeare's Ophelia (who has the final section of this special issue devoted to her) becomes a shared point of reference for girl YouTubers, allowing them to develop a language and ongoing conversation about girl culture, their own identities as girls, and, as O'Neill puts it, "the (im)possibility of authentic expression in the contemporary mediascape." Focusing on how girls represent themselves rather than how popular culture represents them, O'Neill reveals the constitutive role played by Ophelia in girls' self-understanding, providing not only something to identify with, but also to react against. Ophelia thus enables dialogues that are about more than just Shakespeare's girl or girls; she is a launching point for girls' interrogations of contemporary commercial media, allowing girls to "produce and perform postfeminist identities online."

Rachael McLennan's essay on Ten Things I Hate About You, also concerns the use of Shakespeare to construct a feminist identity. The film adapts The Taming of the Shrew to chart not the cultivation of an ideal, passive wife, but the evolving responses of a teenaged girl to a premature and traumatic sexual experience. The culmination of this process occurs when Kat authors a Shakespearean sonnet: a sonnet whose merits, as McLennan argues, have been overlooked and underappreciated in the numerous critical discussions of this film. The sonnet reflects Kat's girlhood as she navigates between the two poles of her own crisis and empowerment, but it also reflects predicament of 1990s girlhood caught in the aftermath of second-wave feminism and at the advent of neoliberalism.

The second group of essays, entitled "Stage," contains three essays on the stage histories of Shakespearean girls. Caroline Bicks explores the figure Mary "Perdita" Robinson, for whom the name of "Perdita" is not just a recollection of her virtuoso performance of a famous Shakespearean "girl" character, but instead, an allusion to the good name and sexual innocence that she "lost" in her affair with the young Prince of Wales, later George IV. Locating the lingering presence of the Shakespearean Perdita in representations of Mary Robinson, Bicks highlights the interplay between the use of "Perdita" as a euphemism for "whore" and her Shakespearean status as an innocent "child of nature," revealing how her posthumously published Memoirs appropriates the girlhood of Shakespeare's Perdita in order to construct her own girlhood and defend her virgin innocence. Bicks reveals, ultimately, the extent to which girlhood itself both negotiates and is constructed in the interplay and tension between innocence and sexual knowledge, but she also locates a continuum, rather than a polarity, between the identities of woman and girl, as the adult Mary Robinson reclaims but also reshapes her own childhood.

Jo Carney's essay on Desdemona, Toni Morrison's radical rereading of Othello, the product of a collaboration with director Peter Sellars and singer-songwriter Rokia Traoré, reveals how Morrison similarly recuperates the character of Desdemona, damned by Othello as a whore, by shifting the focus to her girlhood. Ever since Sula and The Bluest Eye, Morrison's work has narrated the worlds and experiences of girl characters and has used Shakespeare as an ongoing counterpoint to her own fictions. In Desdemona, Morrison sets out the tension between social expectations of demure comportment and an approved marriage, and the sense of freedom Desdemona enjoys to play in the pond, or to imagine herself as a swan. With her North African maid, Barbary, enabling these acts of girlish wildness and imagination, Desdemona is primed and ready to listen to Othello's tales of adventure. As Desdemona's girlhood, here, is reconstructed not only retrospectively, as an adaptation of Othello, but also from beyond the grave, Desdemona's posthumous freedom enables the recovery of her own lost girlhood.

My own essay on the lost girlhoods of The Tempest concerns the afterlives of Miranda and Ariel on stage and film. A crucial aspect of Miranda's girlhood, I argue, is lost to a longstanding editorial and theatrical tradition that refuses to accept her talking back to Caliban, while the two-hundred-year-long history of casting a girl as Ariel is often dismissed as an outmoded and déclassé theatrical convention. In marked contrast to these suppressions of Prospero's girls, Restoration adaptations of The Tempest added girl after girl to Prospero's island, reflecting the play's overarching concern with girls and girlhood, as it charts the path to Miranda's marriage and Ariel's freedom — domestic reality and girlhood wish.

The three essays in the final group all focus on Ophelia, Shakespeare's paradigmatic girl-as-innocent-victim. Polonius calls her a "green girl, /Unsifted in such perilous circumstance," and Ophelia's afterlife, from the Jailer's Daughter in Two Noble Kinsmen to the performances of Kate Winslet and Julia Stiles, via John Everett Millais and countless nineteenth-century paintings, shaped representations of female madness, as Elaine Showalter has argued. They also inform more contemporary understandings of teen-girl anguish, as Mary Pipher's well-known Reviving Ophelia. The Tiqqun collective, "Raw Materials for the Theory of a Young-Girl," which links the fetish for girlhood in contemporary commodity culture with the triumph of capitalism and the decline of the women's movement, opens with Hamlet's devastating works to Ophelia: "I did love you once." But Natalia Khomenko's essay on Soviet representations of Ophelia offers a startlingly different take on Ophelia as a corrupt and untrustworthy villain. What, in the West, serves as confirmation of her innocent girlhood is transformed, in the Soviet context, into evidence of moral decadence and bourgeois indulgence. This allows for the celebration of Hamlet as a political revolutionary, but it also takes Ophelia quite seriously as a villain. As Khomenko demonstrates, this vilification of Ophelia, however unfair it seems, provides feminist authors post-1991 with a rich opportunity to reclaim and remodel — dare we say revive? — this long-maligned heroine.

Dianne Berg's discussion of Mary Cowden Clarke's Ophelia explores the earliest and most influential attempt to fictionalize Ophelia's girlhood and, interestingly, provides another example of what she calls "abuse" — in this case, not by recasting Ophelia as a villain, but, instead, by promoting her wide-eyed, even vapid innocence, and, moreover, by inflicting upon her a set of traumas that provide extra background for her madness. Ophelia becomes an object lesson in vulnerable girlhood — an example of how important it is to take care of young girls — and part of a general tendency in Cowden Clarke (and in Victorian society as a whole) to underestimate and eliminate the agency of girls by constructing them as material to be molded. But Jenny Flaherty shows how contemporary young adult novels succeed in positively "reviving Ophelia," representing her as a survivor, with strength of character and numerous capabilities, rather than as a fragile victim, even as they use Ophelia's sense of being marginalized and an outsider to resonate with contemporary teenaged alienation. Reading a premodern text and heroine unabashedly through the lens of feminist theory and criticism, these novels thus successfully manage to, as Showalter puts it,"liberate Ophelia from the text."

To liberate Ophelia from the text: this is the project of adapting and appropriating all of Shakespeare's girls. The dream of liberation resonates, as well, with a variety of conditions in which girlhood is experienced. In some cases, girls require liberation from their circumstances: the freedom to be themselves apart from social and familial stricture. In others, girlhood offers a space for freedom, possibility, and creativity before the choices and responsibilities of adulthood. In some cases, girlhood is constrained by a materialistic and capitalist system that seeks to commodify their sexuality for private gain. In others, popular images of the young girl provide a spur and pretext for a satirical and subversive critique of the complicity of the commodification of girlhood with the triumph of neo-liberalism and the ideologically motivated perception of the failure of feminism. As the adaptations and appropriations of Shakespearean girlhood that are collected here engage with and contend against a set of inherited and idealized notions of girlhood that may be traced to Shakespeare, they also reflect the creative energies and independence of thought that Shakespeare himself linked, time and again, with girls.

Hateley, Erica. Shakespeare in Children's Literature: Gender and Cultural Capital. Routledge, 2009. xiii + 218 pp. ISBN 978-0-415-96492-0 (Cloth).

In the Spring/Summer 2006 edition on the theme of "Shakespeare for Children," Borrowers and Lenders published an article entitled "Of Tails and Tempests: Feminine Sexuality and Shakespearean Children's Texts," by Erica Hateley, in which the author examined what she termed the "mermaid-Miranda" figure in literature for children. She closely examined both Disney's 1989 film The Little Mermaid and Penni Russon's adaptation of The Tempest, the young adult novel Undine (2004), arguing that while these texts "seem to perform a progressive appropriation [. . .] they actually combine the most conservative aspects of both The Tempest and mermaid stories to produce authoritative (and dangerously persuasive) ideals of passive feminine sexuality that confine girls within patriarchally-dictated familial positions" (Hateley 2006, 1). In Shakespeare and Children's Literature: Gender and Cultural Capital (2009), Hateley expands these ideas to examine not justUndine, but many other appropriations of Shakespeare for young people, while still maintaining her focus on gender issues within such texts.

In the Introduction, Hateley lays out the critical framework of her text by focusing on both Michel Foucault's concept of the "author function" with regard to Shakespeare's "discursive authority" and sociologist Pierre Bourdieu's work on cultural capital, "particularly as it applies to 'Shakespeare' as both embodiment and marker of its attainment" (Hateley 2009, 10, 11). She introduces the subject of how "the discourse of 'Shakespeare' is put to work in literature for young readers to legitimate gendered difference," arguing that "children's authors deploy Shakespeare, not just as cultural authority, but as cultural authority on gender" (2009, 12, 14, emphasis in original). In other words, Hateley argues that authors of Shakespeare appropriations for children prescribe traditional gender roles for implied readers, using the cultural capital of the Bard to add weight to those prescriptions.

In Chapter 1, "Romantic Roots: Constructing the Child as Reader, and Shakespeare as Author," Hateley examines three prominent nineteenth-century adaptations/appropriations of Shakespeare for children: Charles and Mary Lamb's Tales From Shakespeare (1807), Mary Cowden Clarke'sGirlhood of Shakespeare's Heroines (1850-1851), and Edith Nesbit's The Children's Shakespeare (1897). A treatment of all three of these foundational texts in the genre of Shakespeare for children in one chapter might initially seem overwhelming for a reader. Hateley prevents this, however, by giving a thorough background for each text, but then focusing closely only on each text's treatment of Macbeth. The chapter argues that these texts established patterns of appropriating Shakespeare for children that have lasted throughout the twentieth century, and "thus diachronically contextualize contemporary Shakespearean children's literature and the cultural forces reflected and reproduced by it" (2009, 21-22). This statement also explains why the chapter on nineteenth-century texts is important to Hateley's argument in the rest of the book, which deals almost exclusively with contemporary appropriations of Shakespeare for young readers.

The title of Chapter 2, "Author(is)ing the Child: Shakespeare as Character," is self-explanatory. In it, Hateley examines recent texts for young readers that incorporate William Shakespeare as a character, arguing that though "[f]or academics [. . .] 'Shakespeare' is a signifier or a discourse [. . .] whose personal history and experience are fundamentally irrelevant to the Shakespeare play," within popular culture, "Shakespeare is first and foremost the man whose plays reflect his personality and experience" (2009, 49, emphasis in original). This section includes close readings of Gary Blackwood's The Shakespeare Stealer (1998), Shakespeare's Scribe (2000), and Shakespeare's Spy (2003); Grace Tiffany's My Father Had A Daughter: Judith Shakespeare's Tale (2003); and Peter W. Hassinger's Shakespeare's Daughter (2004), all historical-fiction novels for young readers. Hateley's close readings provide numerous textual examples to support her claim that even though these texts present male and female protagonists and were written by male and female authors, within all of them "masculine readers are encouraged to recognise and ultimately appropriate the cultural authority of Shakespeare," while "feminine readers are encouraged simultaneously to recognise both the cultural value of Shakespeare and his work, and the extent to which their own natural distance from it is authorised by that value" (2009, 81). Though this chapter is comprehensive and useful within the area of novels that include Shakespeare as a character, it can feel removed from the other chapters, which deal exclusively with appropriations of plays.

In Chapters 3, 4, and 5, Hateley settles into the meat of her argument, presenting close readings of appropriations for young readers of three chosen plays: Macbeth, A Midsummer Night's Dream, and The Tempest. The author does an excellent job of explaining the plots of the stories and giving background where necessary: though I was not familiar with many of the children's texts she examined, I never had any trouble following her close readings or her argument. Chapter 3, "'Be These Juggling Fiends No More Believed': Macbeth, Gender, and Subversion," argues thatMacbeth's

Hateley supports this argument by examining such texts as Neil Arksey's MacB (1999), which is basically Macbeth on the soccer field, and Welwyn Winton Katz's Come Like Shadows (1993), in which protagonists Lucas and Kinny experience an actual connection with one of the witches ofMacbeth via a magic mirror. She also does close readings of many other novels in this chapter, exploring specific ways in which feminine subjects are given a culturally subversive, though still passive, reading model, while masculine subjects are given a self-reflexive model. For example, in Arksey's MacB, female readers encounter a powerful and culturally subversive female figure in MacB's ruthless mother (the Lady Macbeth figure), but in the end MacB rejects her influence and blames her as the cause of all his wrongdoing. In Katz's novel, while both female (Kincardine or "Kinny") and male (Lucas) main characters are presented, throughout the novel Lucas is portrayed as a more acute observer and a confident person, while Kinny continually doubts herself, even wondering at times if she is crazy. Hateley aptly comments that "the conclusion of the novel makes clear that if the protagonist has been Kincardine, the hero is Lucas" (2009, 111, emphasis in original). She demonstrates that the male characters in these texts are presented as characters that male readers can identify with in a positive way, while the culturally subversive female characters are presented as evil, unstable, or simply less capable.

Hateley supports this argument by examining such texts as Neil Arksey's MacB (1999), which is basically Macbeth on the soccer field, and Welwyn Winton Katz's Come Like Shadows (1993), in which protagonists Lucas and Kinny experience an actual connection with one of the witches ofMacbeth via a magic mirror. She also does close readings of many other novels in this chapter, exploring specific ways in which feminine subjects are given a culturally subversive, though still passive, reading model, while masculine subjects are given a self-reflexive model. For example, in Arksey's MacB, female readers encounter a powerful and culturally subversive female figure in MacB's ruthless mother (the Lady Macbeth figure), but in the end MacB rejects her influence and blames her as the cause of all his wrongdoing. In Katz's novel, while both female (Kincardine or "Kinny") and male (Lucas) main characters are presented, throughout the novel Lucas is portrayed as a more acute observer and a confident person, while Kinny continually doubts herself, even wondering at times if she is crazy. Hateley aptly comments that "the conclusion of the novel makes clear that if the protagonist has been Kincardine, the hero is Lucas" (2009, 111, emphasis in original). She demonstrates that the male characters in these texts are presented as characters that male readers can identify with in a positive way, while the culturally subversive female characters are presented as evil, unstable, or simply less capable.

Chapter 4, "Puck vs. Hermia: A Midsummer Night's Dream, Gender, and Sexuality," asserts that "[s]pecific sub-plots of Dream are explicitly gendered" (Hateley 2009, 117). One such sub-plot involves what the author terms "Puck Syndrome," which is a narrative that places implied male readers "not only into a position of limited autonomy that is circumscribed by Oberon (the Shakespearean father), but also implicitly prefigures future authority for such readers when they become adults" (2009, 118). Appropriations that display this "Puck Syndrome" include Susan Cooper's King of Shadows (1999), Mary Pope Osborne's Stage Fright on a Summer's Night(2002; part of the Magic Treehouse series), and Sophie Masson's Cold Iron (1998). However, Hateley also explores appropriations that deal with other gendered subplots. John Updike'sBottom's Dream (1969) and Ursula Dubosarsky's How to Be a Great Detective (2004) both feature the "rustics" (the Dubosarsky text focuses on the Pyramus and Thisbe narrative), and stories for teenage feminine implied readers focus more on the "romance" plot dealing with Hermia, Lysander, Helena, and Demetrius: examples include Meacham's A Mid-Semester Night's Dream(2004), Marilyn Singer's The Course of True Love Never Did Run Smooth (1983), and Charlotte Calder's Cupid Painted Blind (2002). After examining all of these texts, Hateley concludes that"Puck may operate as a carnivalesque figure of limited autonomy for pre-adolescent masculine readers, but when children's literature appropriates A Midsummer Night's Dream for adolescent feminine readers, no space is made for autonomous development" and that in these texts "[y]oung men are directed towards a life of the mind, young women towards a life of the body" (2009, 145, 146).

Hateley's final chapter of close reading, Chapter 5, "'This Island's Mine': The Tempest, Gender, and Authority/Autonomy," connects to her discussion of The Tempest and Russon's Undine that appeared in her 2006 Borrowers and Lenders article, but greatly expands both the range of texts treated and the point being made. She states that appropriations of the The Tempest for older child readers usually center on the "child figures" Miranda and Caliban, rather than on Prospero, "offering [these child figures] as figures of identification for the implied reader" (2009, 147). Hateley's choice to view Caliban as a child figure in the play is intriguing and can perhaps be attributed to her views on the "arguably analogous cultural position of children and subjects of colonisation" (2009, 148). In addition to Undine, she also examines Sophie Masson's The Tempestuous Voyage of Hopewell Shakespeare (2003), Dennis Covington's Lizard (1991), Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time(1962), and other novels. She concludes that novels like Lizard and Tad Williams' Caliban's Houroffer "the juvenile masculine subject [. . .] a model of cultural authority which is simultaneously predicated on the sexual subordination of the feminine (intratextual) and cultural authority (extratextual)" (2009, 164), and that novels that imply a feminine reader also comply with this model. While she concedes that "Russon comes closer than L'Engle or Oneal to offering the implied feminine reader a position of autonomy," she nevertheless states that Undine is not "an unequivocally feminist appropriation" because of its "maintenance of unregulated feminine sexuality as dangerous" (2009, 186).

That final statement reflects the main point of Hateley's Conclusion, that no Shakespeare appropriation for young readers that she has so far seen succeeds in escaping the following trap: "[r]ather than offering an imaginative space where categories of subjectivity [. . .] might be contested, appropriations of Shakespeare naturalise normative values, and even make the implied reader complicit in their production" (2009, 187). The author admits that even she is not quite sure what this text would look like, though she posits that it might need to shift away from focusing on specifically gendered characters in favor of a more "ambiguously gendered" character like Ariel (2009, 186). Hateley "looks forward to a text which combines feminine autonomy with the cultural capital of Shakespeare" but in the end concludes that

This book would be of great interest to both Shakespeare scholars studying appropriations of his work for children and scholars of children's literature in general; scholars interested in gender theory and construction of selfhood will also find it helpful. Hateley's close readings are thorough, as mentioned earlier, and her notes provide valuable additional information. Perhaps the only drawback to this text is that the title is in some ways a misnomer: though the book is called Shakespeare in Children's Literature (perhaps because Hateley's text is part of a Routledge series entitledChildren's Literature and Culture, edited by Jack Zipes), it deals mainly with young adult novels, and the Young Adult genre often presents very different subject matter from picture books or novels for readers under ten. Therefore, scholars interested in those areas of literature for young readers might not find as much useful analysis in this book. Nevertheless, this focus on young adult novels means that scholars interested in appropriations of Shakespeare for young adults or gender roles as presented in young adult novels will find this text invaluable.

This book would be of great interest to both Shakespeare scholars studying appropriations of his work for children and scholars of children's literature in general; scholars interested in gender theory and construction of selfhood will also find it helpful. Hateley's close readings are thorough, as mentioned earlier, and her notes provide valuable additional information. Perhaps the only drawback to this text is that the title is in some ways a misnomer: though the book is called Shakespeare in Children's Literature (perhaps because Hateley's text is part of a Routledge series entitledChildren's Literature and Culture, edited by Jack Zipes), it deals mainly with young adult novels, and the Young Adult genre often presents very different subject matter from picture books or novels for readers under ten. Therefore, scholars interested in those areas of literature for young readers might not find as much useful analysis in this book. Nevertheless, this focus on young adult novels means that scholars interested in appropriations of Shakespeare for young adults or gender roles as presented in young adult novels will find this text invaluable.