Avant-garde Technique and the Visual Grammar of Sexuality in Orson Welles's Shakespeare Films

This essay argues that Orson Welles develops an avant-garde visual grammar that is perfectly calibrated to represent the felt reality of an asocial sexuality that runs through Shakespeare's plays. Welles's films systematically depart from the norm of language-based, face-to-face intimacy that is represented by the shot/reverse shot convention. In turning against this social and cinematic norm, Welles opens a filmic space in which to show non-linguistic or pre-linguistic forms of bonding that are rooted in profound connections between bodies that combine aggression and love and that, unlike the normative ties embodied in the conventional shot/reverse shot, are framed as anything but foundational components of a functional social life.

In the pages that follow, I will argue that some of the avant-garde formal techniques used by Orson Welles in his three great Shakespeare adaptations —

Macbeth (1948),

Othello (1952), and

Chimes at Midnight (1965) — should properly be understood as expressions of sexuality insofar as they try to capture and bring to the screen a discourse of sexuality that Welles — as a talented reader of Shakespeare — identifies in the plays.

2 The key element in the Shakespearean discourse of sexuality that Welles translates to the screen is its refusal to assume social intimacy as a sexual ideal. One of the fundamental facts about the modern sex-gender system is that it aims to make sexuality into a functional part of social life by confining its legitimate expression to socially integrating, or even socially foundational, experiences of face-to-face intimacy. In modern societies, within the context of a private, familial life that is set apart from the rest of social life, sexuality has a policed, but nonetheless sanctioned, place as a privileged and highly valued experience (

Luhmann 1998). While this notion of sexual intimacy is certainly emerging in the early modern context, in Renaissance culture it has not yet displaced alternative sexual models to achieve the hegemony it does achieve by the eighteenth century. Shakespeare's plays are remarkable for the ways in which they both register the emergence of intimacy as a sexual ideal and resist or even refuse it in favor of experiences of sexuality that are based on the absence, failure, or displacement of a socially integrating intimacy (

Gil 2006). To use one of Leo Bersani's most forceful slogans for describing sexuality, Shakespeare seems to value sexuality for the way it drives people together without providing the terms for socially functional, face-to-face intimacy between them (

Bersani 1987).

The distinctive art of Welles's Shakespeare films flows from his efforts to develop a visual grammar capable of translating the characteristically early modern experience of the failure of intimacy captured by Shakespeare's plays into the modern idiom of film. Welles's Shakespeare adaptations are striking for the formal techniques they use to highlight character positions and forms of relationship that corrode and erode functionally intimate ties between persons and push instead toward a mysterious, a-social sexuality that is alluring, in part, because it is not part of a socially integrating intimacy. Moreover, this way of reading Welles's Shakespeare adaptations sheds a dialectical light on the rest of the Welles film canon. What Welles seems to have found and valued in Shakespeare's depiction of sexuality is a certain no-holds-barred willingness to push to the social margins, the social limits, the test-cases of normative sociability; to that extent, the Shakespeare adaptations provide a sort of grammar of the non-normative, non-social, inter-personal connections that are the real focus of Welles's entire film oeuvre, from Citizen Kane (1941) through The Third Man (1949) all the way to Touch of Evil (1958).

Bordwell notes that like other film conventions, the shot/reverse shot technique can be modified or even distorted by filmmakers seeking to achieve certain effects. One example of a modification or distortion of the basic shot/reverse shot technique is alternating extreme high angle shots and extreme low angle shots, in which one conversant (filmed from above) appears tiny and the other (filmed from below) very large. This modification of the shot/reverse shot convention obviously tends to signal some warping of the normative face-to-face conversational tie that is caused by a disparity in power or status between the conversants. What is so valuable about Bordwell's account is its suggestion that elaborations of the shot/reverse shot convention — such as the use of extreme high and low angles — amount to moving away from the most intuitive, and most nearly universal, filmmaking vocabulary to a more personal, more arcane film vocabulary, one that therefore feels avant-garde rather than popular. In other words, Bordwell's account helps us to see that, at least with respect to the shot/reverse shot convention, a movement toward the avant-garde can also be read as a movement away from the basic, social norm that the convention, at its most conventional, encodes.

I argue that in his Shakespeare films, Welles develops a visual grammar that systematically denatures and deforms the shot/reverse shot technique in order to explore forms of sexualized bonding that diverge radically from the norm of language-mediated, face-to-face intimacy. By subjecting the shot/reverse shot convention to systematic critique and revaluation, Welles brings an explosion of new social forms to the screen. The new social forms that are liberated in Welles's Shakespeare films are non-linguistic, or pre-linguistic, and are rooted in profound connections between bodies that combine aggression and love and that, unlike the normative ties embodied in the conventional shot/reverse shot, are framed as anything but components of a functional social life. Insofar as these ties are defined by rejecting or rebelling against the cinematic norm of face-to-face, shot/reverse shot intimacy, they simply feel anti-social. But at the same time, these anti-social ties have a positive, felt reality, and Welles's films suggest that the proper name for this positive, felt reality is sexuality. As portrayed in Welles's Shakespeare films, sexuality is an interpersonal force that is defined by its refusal of socially integrating intimacy, and that is valued precisely because it drives bodies together without providing the terms for functionally social ties between them. The central achievement of Welles's Shakespeare films is to develop a visual grammar, a set of counter-conventions, that capture the felt reality of a form of sexual bonding that deviates pleasurably from the norm of language-based, face-to-face conversation that is encoded in the DNA, as it were, of Hollywood film.

In Welles's

Othello, as in his

Macbeth, a version of the shot/reverse shot technique is used to denote not a socially functional intimacy, but a socially deviant form of sexualized bonding. But while

Macbeth still asserts the ideal normativity of the face-to-face conversational intimacy generally designated by the shot/reverse-shot convention — by associating it with the long shots in which an ensemble of characters engage in face-to-face interactions with one another —

Othello declines altogether to assert the norm of face-to-face, conversational sociability. In

Othello, Welles defines a visual grammar that re-fashions the shot/reverse shot into a sign of alluring social dysfunction by setting it against another, equally non-conventional mode of interpersonal bonding that is captured by the avant-garde visual technique of cinematic montage. On the one hand, the compression achieved by montage sequences has the virtue of providing a cinematic parallel to the tumbling, narrative acceleration of Shakespeare's own play, which seems to lose time as it unfolds, an effect that many critics of the play have noted. The film's montages, in other words, suggest a tumble of events that can barely be sorted out into a coherent chronology. But on the other hand, in the context of the film's depiction of sexuality, the montage sequences convey a highly unconventional social field that acts as a foil for the highly unconventional intimacy designated by Welles's shot/reverse shots; in that sense, the use of montage in

Othello allows Welles to leave behind altogether the social world grounded in the celebration of face-to-face, language-mediated intimacy.

To illustrate the principle of montage at work in Welles's film, it is enough to look at the buildup to the Venetian council scene. In this sequence, Welles weaves together a series of seemingly disconnected shots of piazzas and buildings, some quite recognizable (like St. Mark's), others not recognizable at all; he gives a shot of Brabantio and his allies spiraling down a staircase, but also a shot of a small band of men crossing a piazza as a flock of pigeons circles overhead (figures 11-14).

|

| Figures 11-14. Montage of Venice in Othello (Welles) |

Of course, this sequence does convey a (somewhat foreshortened) narrative development, but as a montage the meaning of the whole grows steadily as an array of separate shots accrue in the mind of the viewer to form a striking, if cinematically unconventional, tableau of Venetian social energy, grandeur, and power. The montage technique is also evident in the film's opening scene of the funeral processions for Othello and Desdemona, interspersed with shots of Iago hoisted into the sky in a small cage. As Anthony Davies notes, these opening shots announce a break in the mechanisms of narrative filmmaking insofar as they substitute the end of the film for the beginning, something Welles also does in

Chimes at Midnight (

Davies 1988, 101). I would add that this opening sequence, like the buildup to the Venetian council, also breaks with the narrative mode of filmmaking in a more radical sense, insofar as meaning here does not accrue (or not only) from seeing an unfolding chain of events; instead, the meaning of these scenes accrues as a series of striking images build up in the mind of the viewer — an upside-down shot of Othello's frozen face, Othello's black-clad funeral procession, Desdemona's white clad funeral procession, priests bearing tall, thin crosses, confusingly swarming crowds, and Iago hanging above the town square in a tiny cage that casts a (non-narrative) shadow across subsequent scenes in which it hangs in the background, silent and as yet empty (figure 15).

|

| Figure 15. Iago's cage, still empty |

The promotion of montage over the more conventional sequential technique of narrative filmmaking naturally lends the film an avant-garde quality. Davies rightly notes that "

Welles addresses his Othello to an audience whose familiarity with the plot, if not the text of the play, is assumed. It is therefore an adaptation at a more advanced aesthetic level, for the intention is to present visual relationships rather than to visualize narrative connections" (Davies 1988, 102). Anderegg indicts the film for precisely these qualities, seeing in them a pretentious desire by Welles to cast himself as a European cineaste, just as André Bazin had much earlier complained that the film won first prize at Cannes only because of its excessively "academic" nature, and especially its reliance on "

Eisenstein montage" (Bazin 1972, 77). But debating the relative merits of avant-garde and popular filmmaking obscures the way the montage principle functions in the visual economy of Welles's

Othello. What is central to the visual economy of the film is that montage defines a kind of baseline social "health," a mode of sociability that operates as a norm in Venice, but that departs strikingly from the norm of the face-to-face conversational intimacy that is typically encoded in the shot/reverse shot convention.

Obviously, montage violates the shot/reverse shot convention's fundamental technical rule: that characters take turns speaking, so that meaning is created in narrative time. But this technical rule points to the fundamental social rule of normative, face-to-face intimacy, as Bordwell describes it: that persons face each other on a relatively equal footing defined, at a minimum, by a shared language, and that they use this shared language to communicate by speaking and listening, in turn. So conceived, the montage technique displaces, visually, a whole social style, and it is striking that there are essentially no face-to-face conversations in the early scenes in Venice.

|

| Figures 16 and 17. Counselors and Brabantio: Sociability by aggregation |

The mode of interpersonal bonding that is favored in Venice over the private, intimate, face-to-face conversation is a sort of public aggregation in which characters clump together in a single frame in a sometimes haphazard way, speaking at the same time, sometimes not speaking at all, rarely breaking up into smaller, semi-private groups that might have the sorts of intimate, face-to-face conversations that are typically represented by the shot/reverse shot convention. The sociability of aggregation is notably the way in which the Venetian council scene is represented, perhaps inevitably given its status as a large, public gathering (figures 16 and 17), but it is also the way in which Brabantio's response to his daughter's supposed abduction is represented, since he essentially dissolves first into a somewhat chaotic crowd of retainers and then into the crowd of Venetian counselors. Social aggregation is also the way Othello's arrival in Cyprus is represented, an event again marked by the haphazard accumulation of an ever larger group of characters in a single frame (figure 18).

|

| Figure 18. Othello's arrival in Cyprus |

The visual preference for the montage technique that aggregates chronologically unconnected images is, in some obvious way, associated with the social preference in Venice for the aggregation of persons. In other words, the montage style that communicates the grandeur and power of Venice seems also to determine how interactions between characters in Venice are depicted, and when Venetian characters clump together in a single visual field they define a mode of social interaction that favors the open, physical co-presence of many individuals over semi-private verbal exchanges between them.

Though it is not normalized, the Venetian social principle of aggregation is proposed as a norm of sorts and also provides the terms for the Desdemona/Othello relationship while it is still healthy. Before Iago's deception begins to take hold, Othello and Desdemona almost never appear in private, face-to-face exchanges, favoring instead side-by-side, often non-linguistic, often public appearances. Immediately after the opening funeral montage, we see Othello and Desdemona standing silently in a church; next they are ferried silently down a canal in a gondola, only to appear again together in the Venetian council scene (figure 19), which is followed by a shot of them strolling through a piazza side-by-side.

|

| Figure 19. Othello and Desdemona together |

After they are separated by the abortive war, they reappear in the eminently public scene on the shores of Cyprus. It is, in short, the side-by-side appearance, often in conjunction with other characters, that Othello and Desdemona seem to promote visually above any private, one-on-one intimacy.

Against the backdrop of a social mode that works by aggregation, the intimacy of the shot/reverse shot conversation comes to feel like the violation of some primal socio-visual taboo. Framed as a taboo mode of socialization, of course, the shot/reverse shot becomes the perfect visual emblem for Iago's inexplicable, antisocial scheming, and, indeed, from the film's first moments Iago evinces a preference for the semi-private, often whispered, face-to-face conversation; it sets him apart from the baroque pageantry of Venice and identifies him as both relationally sick and the source of relational sickness. As Othello falls under Iago's sway, he is progressively drawn out of the public, aggregating world of Venice — with its visual culture of montage — and into shot/reverse shots that embody an intense sociability founded on an alluringly anti-social intimacy that is repressed in Venice.

The first scene that announces a break with both the visual culture of montage and the social principle of open aggregation is the long, continuous shot along the castle wall in which Iago implants the first seeds of doubt in Othello's mind. Visually, it must be said, this scene comes as something of a relief amid the frenetic editing that characterizes much of the rest of the film, before and after this key moment. The camera rides along next to Welles, shooting at a gently downward angle that levels the conversational playing field by minimizing Iago's (Micheál MacLiammóir's) relative smallness in comparison to Othello's broad, powerful body (figure 20).

|

| Figure 20. Othello and Iago along the castle wall |

This visual impulse toward face-to-face conversational equity is ironic, of course, because it is precisely at this moment that Iago begins his deception and thus inducts Othello into the most distorted interpersonal bond in the film. But what is critical to the visual economy of the film as a whole is that after some 50 seconds of strikingly continuous shooting, the film breaks into its first sustained sequence of canonical shot/reverse shot takes (figures 21 and 22).

|

| Figures 21 and 22. Iago's deception of Othello |

The long shot along the castle wall, in other words, acts as a bridge between two visual styles that are also two social styles, moving from the montages of Venice to the shot/reverse shot style that is largely repressed in the first half of the film, but that comes to dominate the second half. The shot/reverse shots of Othello and Iago talking that follow the long scene on the castle ramparts partake of some of the high/low distortions that also characterize the Macbeth/Lady Macbeth "conversation" that I discussed above; part of Iago and Othello's conversation takes place on a stairwell, for example, and Iago somewhat frenetically darts up and down the stairs past Othello so that he is first above him, then below him, then above again, but never face-to-face with him (figures 23 and 24).

|

| Figures 23 and 24. Othello and Iago's conversation |

But in

Othello, this kind of avant-garde distortion of the conventional shot/reverse shot technique is positively redundant since, when set against a social world whose norms are defined in terms of the visual montage, the shot/reverse shot itself, even at its most canonical, is radically transvalued to signify social deviance or dysfunction.

But even as shot/reverse shots mark a sociability that is deviant in the context of Venetian life, they also emphasize the power and allure of this social deviance. The sheer relentlessness with which Welles cuts together back-and-forth shots of himself and MacLiammóir has the effect of gluing them together visually in a way that exceeds, indeed violates, the relatively loose and open associative principle of montage that characterizes social life in Venice. The intensity of the bonding that Othello and Iago undergo visually is, of course, a rendering of the thematic bonding suggested in the so-called marriage scene (3.3), in which Iago and Othello pledge loyalty to one another. In the film, this marriage scene also marks the beginning of Welles's use of montage sequences that, unlike the sequences at the beginning of the film, are designed to render Othello's subjective derangement.

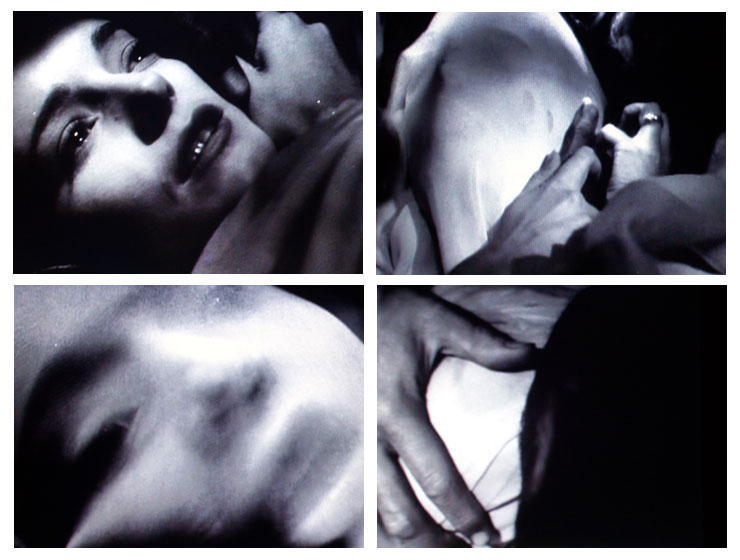

7 When Othello passes out, for example, the camera gives us a series of disconnected and disorienting shots: a castle wall spinning, the ocean beating against the rock wall, birds wheeling in the sky (figures 25-28).

|

| Figures 25-28. Montage as mental chaos |

This agglomeration of shots may be reminiscent of the montage sequences from the first half of the film, but the principle of association here is utterly different. Whereas in Venice, montage aimed to create meaning by associating images and persons with one another laterally rather than narratively, here the montage simply aims to produce the effect of chaos, disintegration, fragmentation, and it does so in order to render a purely subjective point of view — namely, Othello's. It is as if the principle of montage has been infected or colonized, at this point in the film, by a narrative principle that uses montage only to signify an unfolding mental chaos.

8 The subjective disorientation communicated by these late montage sequences is simply the other side of the coin of the intense, face-to-face bonding that Othello and Iago enter into, for the more powerfully Othello and Iago are yoked together, the more consistently Othello is disoriented and therefore disarticulated from the social world he had previously inhabited.

There seems little question that the deviant, socially deranging intimacy communicated by the shot/reverse shots of Othello and Iago has a sexual force. Simon Callow describes Welles's lifelong relationship with Michéal MacLiammóir as following a pattern of triangulated male-male erotic jealousy, a view that might suggest that MacLiammóir's Iago is motivated by sexual desire for Othello and by the jealous belief that Desdemona is getting in the way of his own relationship with his general (

Callow 1995, 88-99). But there is as little evidence of an impulse toward functional homosexuality (in which Othello and Iago would perhaps live happily ever after with the little dog that follows Iago around throughout the movie) as there is evidence of an impulse toward functional heterosexuality. If the relationship between Othello and Iago, Welles and MacLiammóir, is sexual, then it is so only in the rather specialized sense that it is not social, not functional, not integrating. Whatever trajectories of desire are embedded in it, as Welles presents it, Othello's relationship with Iago is, first and foremost, a catastrophically anti-social one, premised on the desire to lie and to be lied to, to use and to be used, to abandon and to be abandoned.

Othello's taste for this kind of sexuality casts new light on the nature of his relationship with Desdemona. The question of sexuality between Othello and Desdemona has long exercised critics of the play. Developing a striking interpretation of the play as an elaborate instance of heterosexual panic, Stanley Cavell argues that there is something profoundly unsettling to Othello about Desdemona's sexual desire for him, and that he essentially chooses jealousy as a way of not acknowledging that desire (

Cavell 1987, 125-42). Welles's film, however, suggests something different, namely that Desdemona's social value crowds out her status as a sex object for Othello. In Welles's film, Desdemona's socially integrating power is marked by the way the couple melt effortlessly into the montages through which Venice communicates its own greatness to itself; Othello and Desdemona do not appear as an intimate couple with a private experience that is sealed off from the public world (which is what Brabantio envisions), but as social pillars whose relationship is fundamentally continuous — even co-assembled with — the public world in which they appear. Visually, this suggests that Desdemona is a sort of cocktail party partner, a trophy wife who seals Othello's acceptance by Venice. But this social fact seems to have tragic consequences for her status as a sex-object for Othello. Perhaps the most striking emblem of the profoundly normalizing effect Desdemona has on Othello is the single fleeting image of them together after the council scene strolling, arm in arm, across a beautiful piazza (figure 29); taken in isolation from the narrative, this shot is a picture of proud, bourgeois, domestic bliss and of a pastoral sexuality that may simply turn Othello off.

9

|

| Figure 29. Othello and Desdemona, arm in arm |

Visually, Welles's film suggests that Othello essentially chooses a deviant intimacy with Iago as a way out of a disappointingly normalizing, essentially pastoral relationship with Desdemona. Or, to put it in the terms of the visual grammar Welles develops here, Othello chooses the deviant intensity of the shot/reverse shot conversation over the cool pageantry of social montage.

And if the appeal of Iago-MacLiammóir is that he offers Othello-Welles a deviant, sexual intimacy, then it is striking that once Othello has tasted this deviant intimacy, he has no trouble transferring it to his relationship with Desdemona. In other words, once he has learned from Iago the pleasurable sociability of the secretive, intimate, face-to-face conversation, Othello applies it more and more frequently to Desdemona, no longer appearing by her side, as he did at the outset of the film, but facing her, locked in intense shot/reverse shot exchanges that are visually identical to the conversations he has with Iago (figures 30 and 31).

|

| Figures 30-31. Othello and Desdemona in shot/reverse shot |

While at the level of the narrative, the closer Othello gets to Iago, the more estranged he gets from Desdemona, at the level of visual technique, Othello's progressive estrangement from Desdemona is communicated in the very same visual vocabulary that is used to communicate his growing and increasingly alluring intimacy with Iago.

Indeed, the Othello/Desdemona relationship gets steadily more passionate as it becomes colonized by the shot/reverse shot technique. Passion here is more or less equated with social dysfunction, and if the scene in which Othello kills Desdemona is among the most sexualized in the film — Othello kisses Desdemona while choking her — this is because it is also the moment of maximum social disconnection between these characters. Watching this sort of thing puts the spectator in a strange position (figures 32-35).

|

| Figures 32-35. Othello and Desdemona in shot/reverse shot |

Kathy M. Howlett sees an invitation to sadistic voyeurism in the film, an analysis that certainly seems apt in relation to Desdemona's death scene. What is especially useful about Howlett's discussion, however, is that she sees this sadism as rooted in the shot/reverse shot technique since, for her, such shots make the spectator oscillate "

between the object choice and identification" (Howlett 2000, 52).10 Howlett is describing the position of the film viewer responding to shot/reverse shots, but it is also true that from Othello's perspective, the intense face-to-face conversations he has with Desdemona in the second half of the film are valuable because they deprive Desdemona of her status as a functional social partner and make her, instead, into a mere object. In the scene in which Othello asks to see Desdemona's hand a few minutes before the murder, for example, the shot/reverse shot technique only emphasizes the intensely (and, to Othello, perhaps, pleasurably) unsettling way Desdemona is put under the glare of Othello's gaze, a process that desocializes her even as it resexualizes her (figure 36).

|

| Figures 36. Desdemona, de-socialized but also resexualized |

In its final scenes, Welles's film completes a narrative arc in which a dysfunctional, sexual sociability that arises in the relationship between Othello and Iago goes on to disrupt, displace, and ultimately to colonize a threateningly functional relationship and a pastoral sexuality that simply turn Othello off. In Welles's film, the alluring, anti-social, and therefore sexual force that glues together first Othello and Iago, and then Othello and Desdemona, is conveyed by a visual economy in which montage, and the cool, aggregating style of social bonding it conveys, are disrupted and displaced by the shot/reverse shot style which here, as in

Macbeth, is cast as the bearer of an alluringly non-normative style of social life.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario