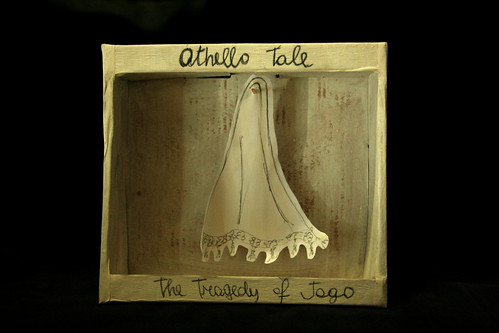

#OthElokuu

|

| Locandina del Festival Verdi 2015 |

|

| Materisle di studio in nostro possesso con... il fazzoletto! |

ATTO I: E così ho cominciato a raccontare a Giacomo, che è il più ghiotto di avventure, la storia di Otello, il "cioccolatte" come lo chiamava Verdi! (non copiatelo, perchè oggi lo insulterebbero tutti accusandolo di razzismo), cioè il moro, mettendo intanto un DVD alla TV (Dir. Riccardo Muti, Teatro alla Scala 2001 - io c'ero!!! - con un Placido Domingo ancora squillante, regia di Graham Vick con meravigliosi ricchissimi costumi di Franca Squarciapino e le scene di Ezio Frigerio; invece nei video vi propongo l'edizione del 1976 diretta da Kleiber). Il suo interesse è stato subito altissimo, grazie all'arrivo della nave con cui si apre l'opera: siamo a Cipro... (giusto per rispolverare le conoscenze geografiche chiariamo con una cartina dove si trova:)

... è sera, davanti al castello di Otello, nuovo governatore dell'isola. È in corso una terribile tempesta e Otello è su una nave. Giacomo subito capisce: verrà inghiottito dalle acque? La folla osserva la nave e prega. Non tutti però. C'è un uomo molto cattivo, che si chiama Jago, che pensa a come vendicarsi perchè Otello gli ha preferito Cassio nel ruolo di capitano. Otello riesce a toccare terra e tutti lo festeggiano. Anche Otello li incita ad esultare per le sue vittorie:

Durante la festa Jago fa ubriacare Cassio e lo incita a provocare Roderigo (che ama segretamente Desdemona, la moglie di Otello)... tra i due si intromette Montano con la spada, ma viene ferito da Cassio. Otello si infuria e degrada Cassio (che così a sua volta ha un motivo per odiare Otello). Otello incontra la sua amata Dedemona e i due si ritirano teneramente avvinti.

ATTO II: All'interno del castello. Jago vuole fare di tutto per rovinare la vita a Otello. Spinge Desdemona a chiedere ad Otello il perdono per Cassio. A Otello, Jago dice di aver visto Cassio parlare con Desdemona... e insinua ad Otello la gelosia! Otello aveva regalato a Desdemona un fazzoletto come simbolo del loro amore. (Giacomo ritorna a seguire la storia grazie a questo elemento concreto... difficile per lui capire il meccanismo della gelosia. Cerco di spostare la sua attenzione sul fazzoletto...). Desdemona perde il fazzoletto. Jago se ne impossessa e lo va a nascondere nella stanza di Cassio. Jago continua a far crescere in Otello la gelosia: ormai Otello è convinto che Desdemona lo tradisca con Cassio, ma manca ancora la prova tangibile.

ATTO III: Otello chiede a Desdemona di mostrargli il fazzoletto regalatole da lui. Desdemona ovviamente non lo trova, avendolo perso. Jago induce Cassio a raccontare le sue conquiste amorose... e fa credere a Otello che Cassio sta raccontando della sua relazione con Desdemona. Cassio ha in mano il fazzoletto! Otello giura di uccidere Desdemona, ancor più quando gli ambasciatori giungono per portare la notizia che Otello deve tornare a Venezia e sarà sostituito a Cipro da Cassio...

E qui Giacomo, che ogni tanto guarda la TV mentre gioc con i LEGO, identificando spesso la parola "Fazzoletto" nelle arie di Placido Domingo ha un'uscita a dir poco esilarante: "Ma lui pensa sempre al fazzoletto!" e ride. In un attimo ha colto l'assurdità della situazione: la gelosia che arriva al punto di desiderare la morte di chi si ama, per colpa di una falsa storia costruita su un fazzoletto!

ATTO IV: Desdemona è inquieta. Si prepara alla notte con la sua ancella Emilia (che è la moglie di Jago... ). Prega e aspetta Otello. Egli giunge colmo d'ira. Dopo averla baciata tre volte, la soffoca col cuscino. Giunge Cassio che intanto ha ucciso Roderigo (che, sempre spinto da Jago, avrebbe invece dovuto uccidere Cassio) e a seguire tutti gli altri personaggi dell'opera. Emilia svela l'intrigo architettato da Cassio e Otello non può fare altro che uccidersi con un pugnale baciando per l'ultima volta la sposa innocente e roso dal rimorso.

È una vera tragedia! Non può finire bene! Ma i bambini, come abbiamo sempre detto e ripetuto adorano le tragedie molto più delle commedie!

Oggi ho fatto trovare a Giacomo, dopo l'asilo, un fazzoletto e gli ho detto che si tratta proprio di quello che Otello ha regalato a Desdemona... ovviamente lui ci ha creduto e non lo molla più!

ATTO II: All'interno del castello. Jago vuole fare di tutto per rovinare la vita a Otello. Spinge Desdemona a chiedere ad Otello il perdono per Cassio. A Otello, Jago dice di aver visto Cassio parlare con Desdemona... e insinua ad Otello la gelosia! Otello aveva regalato a Desdemona un fazzoletto come simbolo del loro amore. (Giacomo ritorna a seguire la storia grazie a questo elemento concreto... difficile per lui capire il meccanismo della gelosia. Cerco di spostare la sua attenzione sul fazzoletto...). Desdemona perde il fazzoletto. Jago se ne impossessa e lo va a nascondere nella stanza di Cassio. Jago continua a far crescere in Otello la gelosia: ormai Otello è convinto che Desdemona lo tradisca con Cassio, ma manca ancora la prova tangibile.

|

| Giacomo davanti a Otello in DVD |

E qui Giacomo, che ogni tanto guarda la TV mentre gioc con i LEGO, identificando spesso la parola "Fazzoletto" nelle arie di Placido Domingo ha un'uscita a dir poco esilarante: "Ma lui pensa sempre al fazzoletto!" e ride. In un attimo ha colto l'assurdità della situazione: la gelosia che arriva al punto di desiderare la morte di chi si ama, per colpa di una falsa storia costruita su un fazzoletto!

ATTO IV: Desdemona è inquieta. Si prepara alla notte con la sua ancella Emilia (che è la moglie di Jago... ). Prega e aspetta Otello. Egli giunge colmo d'ira. Dopo averla baciata tre volte, la soffoca col cuscino. Giunge Cassio che intanto ha ucciso Roderigo (che, sempre spinto da Jago, avrebbe invece dovuto uccidere Cassio) e a seguire tutti gli altri personaggi dell'opera. Emilia svela l'intrigo architettato da Cassio e Otello non può fare altro che uccidersi con un pugnale baciando per l'ultima volta la sposa innocente e roso dal rimorso.

È una vera tragedia! Non può finire bene! Ma i bambini, come abbiamo sempre detto e ripetuto adorano le tragedie molto più delle commedie!

Oggi ho fatto trovare a Giacomo, dopo l'asilo, un fazzoletto e gli ho detto che si tratta proprio di quello che Otello ha regalato a Desdemona... ovviamente lui ci ha creduto e non lo molla più!

Dopo questo ripasso a misura di bambino, sono pronta a rappresentare PVM alla prima di Otello al Teatro Regio alle 19.30 in loggione, in cui incontrerò altri "amici" di PVM: Federica Fanizza di Riva del Garda, che ha invitato PVM ad una presentazione ufficiale a Riva del Garda, Stefania Carrani, prof. di violino a Piacenza (ricordate?)... e un paio di amici della Barcaccia, la nota trasmissione per amanti della lirica di Radio Tre.

Al Cafè del Regio non manca l'affettatrice per il prosciutto:

|

| L'affettatrice del Regio di Parma |

Un Otello è sempre un'emozione. Inoltre, so che mentre io mi godo lo spettacolo dal vivo, a casa, a seguire la diretta TV su TV PARMA, ci sono Antonio e Giacomo e sono certa che Giacomo avrà raccontato il "suo" Otello al papà e ad Antonio.

|

| Giacomo e Antonio seguono la diretta TV |

Il loggione è gremito; è tradizione antica quella delle "prime" in loggione a Parma. Sulla Gazzetta di Parma, il giorno dopo, c'è sempre la cronaca di ciò che accade tra gli appasionati prima, durante e dopo l'opera...

|

| Il loggione affollato |

|

| Dentro al loggione... |

Questa volta ho avuto l'onore di stringere la mano e scambiare qualche parola con una vera "istituzione" del loggione del regio: il signor "Gigetto", che non ne perde una di rappresentazione e dice la sua con competenza su tutto e su tutti in dialetto parmigiano. Uno spettacolo nello spettacolo che ancora oggi per fortuna esiste e aiuta a mantenere ancorato alla memorabile tradizione il Teatro regio di Parma, che barcolla, ma per ora non cade, nonostante ci si mettano tutti (i politici) a tentare di abbatterlo insieme a tutta la cultura musicale italiana che in ambito operistico è la prima nel mondo.

|

| Gigetto e il giornalista della Gazzetta con taccuino |

E che sia la prima nel mondo lo testimonia il nutrito gruppo di coreani che mi ritrovo a fianco e alle spalle, raccolti in formazione compatta per sostenere il debutto nella parte del protagonista del loro connazionale Rudy Park, che con coraggio ha accettato il delicato ruolo dopo il forfait di ben altri due tenori. L'orchestra, diretta dal Maestro Daniele Callegari, s'impone immediatamente con un volume sonoro notevolissimo (per alcuni eccessivo... "io suonerei ancora più forte" ha commentato a fine I atto, ad alta voce con la tipica "r" moscia parmigiana, un loggionista alla mia destra) accresciuto dalla raccolta atmosfera del regio di Parma, che mi mancava dopo l'ampiezza per me eccessiva della Staatsoper viennese. Il sipario si apre sulle scene di Pier Luigi Pizzi, artista di grande esperienza e sempre elegante e raffinato, che ha curato anche regia e costumi. Scene vuote, geometriche, minimaliste, con mura, tavolini, porte e trono dagli angoli retti e tutti sulla tonalità del beige/giallo ocra tranne le porte marroni scuro del III e IV atto e gli alberi scuri nel II atto, adornati da luccicanti foglioline dorate e il letto a baldacchino della magnifica scena/quadro finale. Mi è piaciuto tutto di questa regia, anche i costumi avevano la leggerezza di veli color pastello (giallo, bianco, rosa chiaro, arancione in diverse sfumature) e tra di essi spiccavano alcuni costumi viola: fatto curioso perchè in teatro il viola è colore scaramanticamente da sempre evitato. Nere le figure dei personaggi-pedine di Jago, lui stesso in nero, con tute stile motociclisti in pelle, che spiccavano tra gli acquarelli degli altri personaggi. Più sontuoso il doge. Curati anche i dettagli: il fazzoletto decorato, le acconciature, i fiori, gli arredi scenici e le armi. Giusti i movimenti delle masse e anche quelli dei protagonisti, mai eccessivi ma nemmeno immobili in proscenio. Peccato che la figura di Otello a causa della corporatura massiccia del cantante unita ai tratti somatici e alla capigliatura orientali lo abbiano reso più "Samurai" (anche se coreano e non giapponese) che Moro, soprattutto nel finale, armato di sciabola. Il loggione non ha gradito la regia, ma sul fattore scenico non ho paura di dissentire: ne capiscono di voci e di musica, ma quanto a scene/regia/costumi non sono altrettanto credibili. Mi sento più esperta io, anche grazie agli studi fatti in Università e ai seminari che ho seguito per anni tenuti da Maestri indiscussi della regia.

Delicatissima la Desdemona di Aurelia Florian, notevolmente migliorata dal punto di vista tecnico e a mio avviso ingiustamente buata dal loggione a fine spettacolo. Park ha fatto del suo meglio, scritturato all'ultimo e buttato sul palco di un Teatro che su Verdi non perdona ha avuto molto coraggio e nessuno alla fine ha osato sottolineare la scarsa duttilità della sua potente voce, che ha cantato nello stesso modo da inizio a fine opera, senza mai riuscire a utilizzare le mezze voci che le parti liriche dell'opera richiederebbero. Tuttavia il mezzo vocale è notevole e l'intonazione corretta, ottimo il fraseggio, certamente con l'esperienza potrà migliorare in espressività e soprattutto ha molta strada da fare per quanto riguarda l'interpretazione da attore. I suoi movimenti, i suoi sguardi, i contatti con Desdemona... tutto troppo "rigido" e di conseguenza poco coinvolgente. Un Otello di cui, da donna, non ci si innamora. Il povero Marco Vratogna, Jago, è stato il più criticato dal loggione. Sicuramente è inciampato lui stesso sul "fazzoletto" che crea da secoli problemi seri ad Otello nella trama e a lui ha giocato un brutto tiro in una breve frase del III atto ("Il fazzoletto"...) in cui la voce gli si è spezzata provocando un sonoro dissenso del loggione. A parte quell'inciampo non ho trovato la sua prova a tal punto catastrofica da giustificare i "BUUU" piovuti dall'alto, anzi, aveva una bella presenza scenica ed era perfettamente nel ruolo del "cattivo"... ma dobbiamo sempre pensare che questi signori loggionisti hanno alle spalle un'esperienza decennale di spettacoli, anche di un'epoca ormai ahimè lontana in cui il teatro e il mondo dell'opera avevano i mezzi per essere l'eccellenza. Oggi questi cantanti sono sballottati di teatro in teatro per poter guadagnare cifre dignitose e forse si dedicano meno allo studio paziente, fanno meno gavetta e pochissime prove ormai in quasi tutti i teatri, sempre per lo stesso motivo: NON CI SONO SOLDI! Perchè ormai il mondo va nella direzione del profitto e basta; la cultura fine a se stessa pare non abbia più alcun senso e a testimoniarlo sono i dibattiti degli ultimi tempi sul Liceo Classico, che ormai viene scelto da quattro gatti nostalgici del bel tempo che fu...

|

| I bambini del Coro |

I bambini del Coro di Voci Bianche sono stati fin troppo bravi, se pensiamo all'educazione musicale (IL NULLA) che c'è nelle nostre scuole.

Solidissimo il Coro del Teatro del Maestro Faggiani, che come sempre è stato ineccepibile. Al loro posto dignitosamente tutti gli altri.

Per concludere: con i tempi che corrono un Otello così è più che dignitoso. È un segnale di speranza per una rinascita dei tesori che fanno dell'Italia uno dei paesi culturalmente più ricchi al mondo. Verdi è il nostro orgoglio e al Teatro regio di Parma lo sanno. Otello resta una delle opere più belle di Verdi e una delle più affascinanti in assoluto.

|

| Applausi finali |

|

| Il Cast schierato visto dalla mia postazione |

IL LIBRETTO

A ciò contribuisce anche il superlativo libretto di Arrigo Boito su quale, da letterata, vorrei soffermarmi proponendovi alcuni versi che io trovo particolarmente belli. Il libretto di Boito non declassa Shakespeare (in Macbeth i versi di Maffei sono di livello molto inferiore), anzi mantiene la vivacità lessicale e la musicalità del verso. L'italiano di Boito è una meravigliosa lettura che procede insieme alla musica di Verdi in un continuo intreccio per cui l'uno arricchisce di significati l'altra e viceversa. Il lessico fa venire nostalgia dell'antica ricchezza della nostra lingua oggi così inaridita e impoverita.

JAGO: "Suvvia, fa' senno, aspetta l'opra del tempo. A Desdemona bella, che nel segreto dei tuoi sogni adori, presto in uggia verranno i foschi baci di quel selvaggio dalle gonfie labbra".

OTELLO: "Venga la morte! E mi colga nell'estasi di questo amplesso il momento supremo!"

JAGO (il monologo): "Credo in un Dio crudel che m'ha creato simile a sé e che nell'ira io nomo. Dalla viltà di un germe o di un atòmo vile son nato. Son scellerato perchè son uomo; e sento il fango originario in me. Sì! Questa è la mia fé! Credo con fermo cuor, sì come crede la vedovella al tempio, che il mal ch'io penso e che da me procede, per il mio destino adempio. Credo che il giusto è un istrion beffardo, e nel viso e nel cuor, che tutto in lui è bugiardo: lagrima, bacio, sguardo, sacrificio ed onor. E credo l'uom giuoco d'iniqua sorte dal germe della culla al verme dell'avel. Vien dopo tanta irrision la Morte. E poi? E poi? La morte è il nulla. È vecchia fola il ciel."

OTELLO: "Più orrendo d'ogni orrenda ingiuria dell'ingiuria è il sospetto. "

JAGO: "Seguia più vago l'incubo blando; con molle angoscia; l'interna imago quasi baciando, ei disse poscia: il rio destino impreco che al Moro ti donò. E allora il sogno in cieco letargo si mutò"

Otello: "E tu... come sei pallida! E stanca, e muta, e bella. Pia creatura nata sotto maligna stella. Fredda come la casta tua vita e in cielo assorta."

LA MUSICA

La musica si esprime in tutta la sua violenza e si fa grido, da subito, quando siamo letteralmente invasi dalle acque della tempesta contro cui lotta Otello. Improvvisi schianti sonori che inondano platea e palchi con un'irruenza inaudita nelle precedenti opere di Verdi. E forse per questo non è da criticare la lettura veemente di Callegari di ieri sera. Grandioso anche il finale del III atto. Potenza che diviene dissolvenza nei momenti lirici con archi in tremolo e flebili fili di fiati. Il discorso musicale si fa unico, non più suddiviso in Arie e Cablette... Verdi vira verso l'"odiato" ma stimato Wagner, pur restando assolutamente Verdi e fa uso del "declamato melodico" che sempre più caratterizza le opere avvicinandosi al Novecento. Raffinatissime le scelte timbriche: emergono il violoncello, i contrabbassi, l'oboe, i flauti, i corni ... sempre a sottolineare atmosfere o stati d'animo particolari.

|

| Otello e Desdemona |

|

| Particolare dell'interno del Regio |

PER GUARDARE L'OTELLO DIRETTO DA MUTI ALLA SCALA CLICCA QUI: https://youtu.be/zIVFSW25h1o

PER L'OTELLO DIRETTO DA MUTI A SALISBURGO CLICCA QUI: https://youtu.be/jfzdhNpr2U4

|

| Otello nell'illustrazione di Gabriele Clima |

Otello fa parte di uno dei tre bellissimi libri di Cristina Bersanelli e Gabriele Clima dedicati all'Opera e rivolti ai bambini. Avevamo già parlato di "FILTRI E POZIONI ALL'OPERA" quando abbiamo analizzato "L'Elisir d'amore" di Donizetti: Filtri e Pozioni.

I libri sono editi da Curci Young e li trovate in libreria a 16 euro l'uno.

I libri sono editi da Curci Young e li trovate in libreria a 16 euro l'uno.

Questo volume si intitola "KATTIVISSIMI ALL'OPERA" e raccoglie le storie di altre 5 opere (Macbeth e Otello di Verdi, Tosca e Turandot di Puccini, Don Giovanni di Mozart), raccontate dalla parte dei cattivi. E ovviamente non poteva mancare Jago, che noi conosciamo ormai assai bene e che cattivo, anzi "kattivissimo" certamente è.

|

| Jago |

Jago si presenta: "Onesto e leale: così tutti mi vedevano. Invidia la mia?" e racconta del suo odio nei confronti di Cassio, che come ricorderete aveva ricevuto da Otello il titolo di Capitano che Jago riteneva di meritare al suo posto. E, inoltre, dice di odiare Otello in quanto straniero e lo invidia per la bella moglie Desdemona. Nel libro, Jago (come tutti gli altri kattivissimi) ha anche una Carta d'Identità con tanto di segno zodiacale, ovviamente Gemelli (un segno doppio, giusto?):

Iago vuole rovinare la vita all'odiato Otello, si sente chiamato dal destino a farlo. Sa qual è il punto debole di Otello: è Desdemona, la bella moglie di cui è gelosissimo. Con astuzia Jago fa credere a Otello che Desdemona lo tradisce con Cassio... e gli bastò un fazzoletto:

Iago vuole rovinare la vita all'odiato Otello, si sente chiamato dal destino a farlo. Sa qual è il punto debole di Otello: è Desdemona, la bella moglie di cui è gelosissimo. Con astuzia Jago fa credere a Otello che Desdemona lo tradisce con Cassio... e gli bastò un fazzoletto:

... che per Otello aveva un significato particolare, era un pegno d'amore. Lo rubò dalle mani di Emilia, sua moglie e ancella (dama di compagnia) di Desdemona. E poi lo mise in casa di Cassio: ecco la prova tangibile del tradimento costruita ad arte! E infatti Otello va su tutte le furie e il suo immenso amore per Desdemona si tramuta in feroce odio fino ad arrivare ad ucciderla in un modo spietato:

Jago ha anche predisposto un agguato per sbarazzarsi di Cassio, ma tale piano fallisce e Cassio sopravvive. Così qualcosa va storto e Jago viene smascherato. otello scopre di aver ucciso un'innocente e non gli resta che uccidersi.

Al termine del libro c'è una pagina dedicata ai compositori delle opere scelte in questa raccolta e un CD AUDIO che contiene i racconti intervallati da alcuni brani delle opere.

|

| La nostra selezione di carte |

|

| Le 6 carte di Otello |

Ecco un'immagine dell'avvincente sfida:

Ascoltiamo Jago nell'Otello di Verdi interpretato da Leo Nucci:

|

| Marco e Giacomo nel palco del Regio |

PVM torna al Teatro per bambini: Teatro Regio di Parma per l'ultimo appuntamento di VerdiYoung: "Otello", una produzione dello stesso teatro e di "Zazì", Laboratorio Creativo per Bambini: http://www.zazi.it/: "Il Gioco dell’Opera", l’opera raccontata ai bambini delle Scuole dell’Infanzia. La regia e il testo sono di Veronica Ambrosini, i costumi del Teatro Regio di Parma e gli interpreti sono Allievi del Conservatorio Arrigo Boito di Parma, nella classe della Prof.ssa Donatella Saccardi.

Prima uscita con le nostre magliette, che hanno suscitato un certro interesse, anche grazie al fatto che eravamo ben in sei ad indossarle: Antonio, Giacomo ed io e Marco, Valeria e la loro mamma, carissimi amici di PVM, Grazie!:

|

| Le magliette di PVM |

|

| "Gli arancioni" di PVM guardano e ascoltano Jago |

|

| Antonio e Valeria entrano nel palco |

|

| Antonio e il Burattino/Attore Cassio nel palco a fianco! |

|

| Marco e Giacomo |

|

| Antonio, Valeria e mamma Stefania sotto di noi |

I burattini/attori si muovono nei corridoi della platea, ma in più di un'occasione entrano in un palco del teatro. Ci si sente così "dentro" lo spettacolo. I bambini guardano meravigliati di qua e di là girandosi sulle poltrone seguendo le voci. Idea bellissima e molto ben realizzata.

|

| Otello nel palchetto |

Chiedo perdono per i video rubati, ma rendono l'idea della bellezza dello spettacolo! Anche se sono di pessima qualità.

Otello e Desdemona, duetto "Già nella notte densa" - Atto I

Gli allievi del Conservatorio hanno fatto del loro meglio. Sapete sicuramente che Otello è una delle opere più complesse da affrontare. I ruoli non sono certo stati scritti per studenti. Complimenti dunqye anche ai ragazzi (tutti Coreani) che hanno il coraggio di mettersi alla prova con pagine così ardite.

Jago "Credo in un Dio crudel" - Atto II

Ricapitolando... Otello ama Desdemona. Jago odia Otello. Emilia è la moglie di Jago e ancella di Desdemona (le è fedele ed è buona non come il marito!). In questo breve spezzone il dialogo tra Cassio ed Emilia: Cassio vuole chiedere a Desdemona di perdonarlo per aver ferito, da ubriaco, in un duello Montano, cosa che ha fatto infuriare Otello...

Jago trama contro Otello mettendogli in testa il sospetto che Desdemona lo tradisca con Cassio. Per fare questo utilizza un fazzoletto caduto dalle mani di Desdemona, che viene da lui messo tra le mani di Cassio come prova tagibile del tradimento di Desdemona.

|

| Otello vede dal palco Desdemona con Cassio... |

E alla fine dello spettacolo la nostra amica Valeria si è fatta mostrare da Emilia Pupazzo/attrice il fazzoletto di Topolino.

|

| Valeria e Antonio tra i pupazzi |

Trionfo meritatissimo, applausi e "Bravi!" a cui PVM si unisce senza le riserve dello spettacolo precedente (Il viaggio di Milo e Maya), del quale questo è senza dubbio (a nostro unanime giudizio) di livello molto superiore da tutti i punti di vista. Un modo intelligente di avvicinare i bambini al mondo dell'opera, forse ancora più efficace della formula pensata dal Teatro alla Scala. Se solo questi attori avessero a disposizione mezzi musicali maggiori (ad esempio un pianoforte a coda e qualche strumento in più) la magia raggiungerebbe l'apice. È giusto sfruttare questo tipo di spettacoli come "palestra" per studenti/cantanti. Anche loro, sostentuti da un accompagnamento più corposo, potrebbero essere più sicuri, anche se hanno tutti fatto la loro parte dando il massimo (e il risultato è stato sinceramente di buon livello) già con il solo pianoforte verticale. Bravi! agli allievi della Prof.ssa Donatella Saccardi.

È una gioia uno spettacolo così. È la prova che il teatro, se "usato" bene, se "fatto" bene, ha ancora un potere infinito sui bambini. È un 3D naturale, in diretta, senza bisogno di occhiali e di costosi apparecchi video. Bastano 5 euro per assistere allo spettacolo... e poi vedere il bellissimo Teatro Regio, stare in compagnia di amici e/o farsene di nuovi con cui condividere queste belle esperienze, e conoscere un capolavoro della storia della letteratura teatrale (l'Otello di Shakespeare) e un capolavoro dell'Opera Lirica (l'Otello di Giuseppe Verdi su libretto di Arrigo Boito tratto da Shakespeare, appunto...)!

Qui potete vedere le immagini della prima messinscena di questo spettacolo dell'Ottobre 2009: https://flic.kr/s/aHsjovU5HF

Qui potete vedere le immagini della prima messinscena di questo spettacolo dell'Ottobre 2009: https://flic.kr/s/aHsjovU5HF