Abstract

"Boot Camp Shakespeare," by Georgia Shakespeare, introduces children from the ages of four to eight years old not only to Shakespeare but also to the craft and mechanics of theater. An improvised ensemble piece, "Scary Field Trip," turned Iago's ostensible motive for revenge, his anger at being passed over for promotion, into the fury of a "nerdy" kid tricked by his "cool" classmate. Although "Scary Field Trip" did not engage directly with the racial plot of Shakespeare's play, its casting practices and the structure of the appropriation itself nonetheless did so.

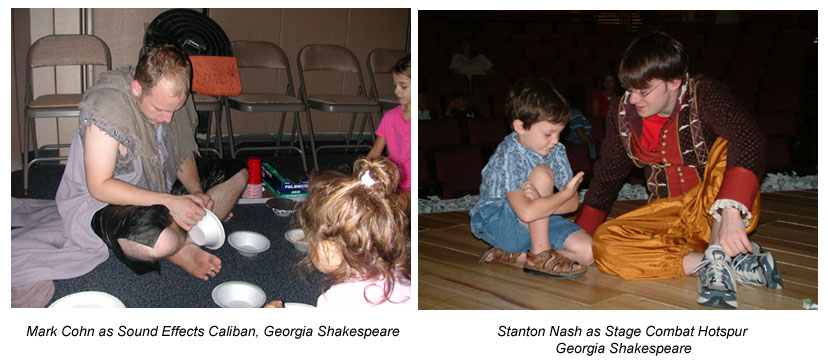

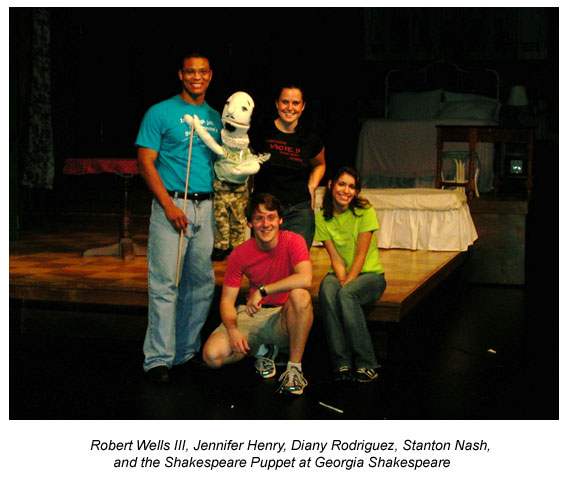

"Scary Field Trip," improvisation by Jennifer Henry, Stanton Nash, Diany Rodriguez, Robert Wells III. "Boot Camp Shakespeare." Georgia Shakespeare. Oglethorpe University, Atlanta, Georgia. August 3, 2005.

The essays in this issue of B&L not only consider the specifics of presenting Shakespeare for Children, but also question the purposes of doing so. Shakespeare camps, coloring books (indeed, competing coloring books by Bellerophon [A Shakespeare Coloring Book 1983] and Dover [Green and Negri 2000]), picture books, stuffed toys and other tools target an ever-younger consumer. The BBC's CBeebies website, aimed at preschoolers, features a Flash animation sequence of A Midsummer Night's Dream, under the rubric "Fairy Stories" (other stories include folk tales from around the world, such as "Rumpelstiltskin," "The Rupee Tree," and "Hansel and Gretel," and commissioned stories, such as "Treasure Pie"). In most of these instances, "Shakespeare" signifies on the one hand literacy — in Disney's Baby Einstein DVDs, for instance, Baby Einstein: Baby Shakespeare World of Poetry (2002) introduces toddlers to simple words and the alphabet song through the mischief of "Bard, the friendly dragon" — and on the other hand, literariness, since Baby Shakespeare also includes voice-over poems by Robert Frost, W.B. Yeats, Langston Hughes, William Wordsworth, and, of course, Shakespeare. The British "Key Stages" of education, which require every student to have read a Shakespeare play before graduation (some accounts have it, before age ten), have lent a peculiar urgency to the quest for ever-more accessible Shakespeare in Britain (as Sheila Cavanagh notes in her essay in this issue).

The British company "Shakespeare 4 Kidz: The National Shakespeare Company for Children" performs and merchandizes abridged Shakespeare plays with added songs, dances and so on for and to British elementary schools. These productions deliberately eschew textual accuracy in favor of retaining the main plot, sub-plots, and minor characters. (Their Macbeth, however, retains the witches' song in its entirety, including its offensive reference to "Liver of blaspheming Jew," an interesting comment in itself on transatlantic notions of what is appropriate in an elementary-school setting. I'm not suggesting that the company bowdlerize, but I note that the teachers' kits sold with the "Play Pack" include no suggestions on how to direct possibly animated discussions in a diverse classroom that might well include some so-called "blaspheming Jew[s]" or "Turk[s]").

|

| Georgia Shakespeare's Shakespeare Puppet |

The purpose of Shakespeare in "Shakespeare 4 Kidz" is, quite literally, national accreditation, on the part of the schools using the "Play Packs" and hosting the performances. And the reasons behind the enshrinement of Shakespeare (the only required author, at the time of this writing) in the British National Curriculum must necessarily remain mysterious. But there is clearly an element of wishful thinking, of the desire for a shared body of knowledge, of a desire to reclaim Shakespeare for England and for Englishness. At its worst, this impulse produces drama and criticism at its most conservative. But at its best, it could lead to re-evaluations of what we "mean by Shakespeare" (Hawkes 1992) in the classroom and on stage. Consider the Royal Shakespeare Company's year-long season of the Complete Works, which re-canonizes Shakespeare and his works as the heart of British theater, only to stretch the limits of what we might consider "Shakespeare" or even drama, to encompass ballet; opera (The Sonnet Project[Bryars 2006]); Polish ensemble theater (Macbeth); Indian folk theater (A Midsummer Night's Dream); musical theater (Merry Wives) and "responses": Hamlet: Tiny Ninjas (Weinstein 2006); King Lear: Yellow Earth (Ka-Shing 2006); the Baghdad Richard (Al-Bassam 2007), and others.

"Boot Camp Shakespeare," a summer workshop run by the Georgia Shakespeare Festival, ostensibly presents live Shakespeare to children aged four to eight. I say "ostensibly," because what the camp really does is to use "Shakespeare" as the excuse to offer young children a preliminary approach to the craft and mechanics of theater and even to the emotional exercise of character acting. The children spend the first part of a hot summer morning in July or August working with actors from the festival on acting, stage combat, properties, sound effects, lighting, costume, and ensemble work; after a break for juice and cookies, they watch short scenes from the plays, performed by the Georgia Shakespeare actors, and then return to their work groups briefly before participating in a short performance — an appropriation of Shakespeare previously improvised by the young actors. Shakespeare himself appears as a large, soft, stick puppet, dressed as a drill sergeant in camouflage pants — but with Elizabethan ruff and quill pen — mustering his infantine troops for performance.

Upon entering the theater, children are asked to choose a color-coded activity, each led by a costumed actor personating a character from one of the plays, usually performed for laughs, but always ready with some verse appropriate to his or her activity. Katharina, leader of the red group, was in charge of acting; Hotspur (white) of stage combat; an ebullient Lady Macbeth (yellow) made elaborate props out of balloons; Caliban (orange) engineered "sounds and sweet airs" with improvised maracas made from paper bowls and plates, aluminum foil, and dried beans; Goneril and Regan (green) shone flashlights through cups to generate eerie lighting effects; Queen Margaret (blue) manufactured hats and costumes out of common household items, and Adriana (black) drilled her young troops in ensemble work.

|

The scene presented on the day I attended (with toddler in tow) came from Othello. The cast performed first a short section of the so-called temptation scene (3.3), which they explained to their young audience as Iago's attempt to revenge his feelings of exclusion and bitterness when Othello passes him over for promotion — a revenge that, however, vastly exceeds the original offense. The plot of the appropriation of the scene, "Scary Field Trip," based on improvisations by the actors, concerned the group dynamics of a school field trip to a dinosaur museum, during which a group of "cool" kids exclude the "nerdy" ones, alternately mocking and ignoring them. The dialogue was improvised around a loose script that allowed each child in the camp to participate. The parts of Robert (the coolest kid), Stanton (the nerdiest kid), Ms. Rodriguez (the schoolteacher), and Jen (the museum curator), were played by Georgia Shakespeare actors (using their own names), but children composed the groups, performed as cool and nerdy friends, made "scary" sound and lighting effects (with improvised maracas and paper-covered flashlights), used long balloons to make dinosaur bones, and faked fights.

|

The story begins when Robert, the coolest kid, plays a trick on the nerdiest one, Stanton, by pretending to be the voice of a dinosaur in the museum that has come to life. Angered by the subsequent laughter at his expense, Stanton becomes furious, enacting a revenge that, like Iago's, is disproportionate to the initial offense: he destroys the entire dinosaur exhibit, and frames Robert for the crime. At the end of the episode, the weeping Robert's tears are wiped with a handkerchief as his teacher urges him to "confess." As the actors explained afterwards, the curator and schoolteacher assume the cool kid's guilt based on circumstantial evidence (he "was in the wrong place at the wrong time," as "Scary Field Trip" suggests), just as Othello assumes Desdemona's guilt, based on the handkerchief.

Although the actors mentioned neither Othello's skin color nor issues of race directly, the same Afro-descendant actor who played Othello played Robert, the cool kid and eventual victim of Stanton's machinations. The improvisation thus engaged present-day assumptions about black skin ("coolness," at the beginning of the playlet, and perceived criminality at the end) to correspond to the beliefs about blackness animated in Shakespeare's play (admirable military prowess, on the one hand, and credulous jealousy on the other). In this unspoken parallel it reminded me of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival's abbreviated Othello performed at the (US) Shakespeare Association in March 1999. That forty-minute, three-person touring version of the play for high schools excised the language of racial insult and skin color from the play, a controversial decision defended by the company on the grounds that the children in the schools they visited were already alert to the possibility of racial hatred directed towards interracial marriages without the theater company adding, as it were, insult to injury ("Forty-minute Othello"). I believe that might be true for many actors and viewers of color present at both productions — and yet — and yet — I wonder whether we nonetheless need to spell out the implications of color-conscious casting. That the improvisation, first, turned out the way it did and, second, worked as well as it did depended upon our assumptions about race in Atlanta. "Boot Camp" children are a little young for such a discussion, but it is almost impossible to engage Othello meaningfully without it.

The metaphorical resonances of the "Boot Camp" model and Drill Sergeant Shakespeare are likewise peculiar, but compelling. On the one hand, the analogy suggests, Shakespeare study requires basic training, and that training will be sudden, rigorous, even hectoring. On the other, such training will be familiar, down-to-earth, and above all US American. The puppet itself is soft, like a well-loved toy, and it presents Shakespeare literally in camouflage, as though this is a way to make Shakespeare blend in with its surroundings. In Georgia Shakespeare's "Boot Camp," then, Shakespeare comes to stand not for Englishness (as in the British National Curriculum) but for theater itself. And if spoken drama is to avoid the fate imagined by Richard Schechner, of becoming the twenty-first-century equivalent to the string quartet or chamber chorale, then the earlier that children encounter such an introduction, the better.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario