I have long considered myself a Shakespeare nut, but, in reality, whenever I read Shakespeare, I end up reading one or other of a favourite dozen or so. So, about a year ago, I determined to read all the Shakespeare plays, roughly in the order in which they were written. I say “roughly”, as we cannot be sure of the exact order. I decided to follow the order in which the plays are presented in the Oxford Shakespeare, edited by Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor. That edition, I realise, has its detractors, but the order in which it presents the plays is possibly as good a chronological order as any. The plays themselves I read in the individual Arden editions.

I have now finished the project (it took me nearly a year), and I made notes as I was reading them. These notes, while far from being erudite exegeses – I am certainly no Shakespearean scholar – do, at least, capture what I, an enthusiastic amateur, made of them. And I have decided to polish up those notes a bit, and put them up on my blog, play by play.

Isn’t it astonishing the difference that even a slight re-wording can make? Shortly before Desdemona is killed, Othello tells her she is on her death-bed. In most editions, Desdemona replies “Aye, but not yet to die”. This gives the impression that she is responding to Othello in a calm and collected manner, and discoursing with him. But in both the Folio and in the Quarto text, she replies “I, but not yet to die”. This obviously makes little sense, and one can see why most editors change the “I” to “Aye” (ie "yes"). But in the Arden edition, the editor, A. J. Honigmann keeps the “I”, but re-punctuates it so it reads “I? – But not yet to die!” So now, Desdemona is not discoursing with the man about to kill her – she is beside herself in blind terror, and is shrieking incoherently in panic. Of course, she doesn’t stand a chance. “I hope you will not kill me,” she says with a sort of child-like innocence before she has had the chance to take in the full horror of the situation. And soon, she is pleading desperately with all her might: “Kill me tomorrow, let me live tonight!” But it is no use. In full view on stage, Othello drags this screaming, terrified woman, an adolescent still almost a child, back to her bed and strangles her. It is horrible. Even if Desdemona were be guilty of what has been alleged, it is horrible even beyond what may be imagined. And Shakespeare forces us to watch it being done.

And yet, isn’t it curious that the man who commits so horrendous an act even before our eyes should command such sympathy? That we can refer to him (as so many do) as the noblest tragic protagonist that Shakespeare had created? In real life, a man who murders his helpless teenage wife (for, as I shall go on to argue, I cannot see Desdemona as anything other than very young – possibly about sixteen or so) would, quite rightly, be regarded as a monster. Most of us, I imagine, would close our ears to any possible mitigating factor. So why do we not feel that way about Othello?

To answer this question one must peer deeply into some of the most complex characters that even Shakespeare ever created. Indeed, so complex are they that no two readers, and no two members of the audience, can have the same view of them. And no matter how often one reads or sees this play, one comes away with a changed perception from the last time – one’s mind becomes a seething cauldron full of different possibilities.

That doesn’t mean, of course, that any interpretation is correct. I’ve read too many accounts of this play that are just wrong – some embarrassingly so. (I read a profoundly embarrassing column in the Guardian blog some time ago advising Lenny Henry not to demean himself by playing Othello, as Shakespeare had merely written a racist stereotype.) One rule of thumb is that any interpretation that is simple is bound to be wrong. Shakespeare knew not merely the complexity of human character, but also the essential mystery at the centre of it.

It seems to me that if this play is “about” anything at all, it is “about” damnation. Throughout the play there are references to hell and heaven, to demons and angels, to salvation and to damnation. The play is about how we forfeit our very souls, by allowing evil to enter. At the centre of this play is the damnation of Othello’s soul. No matter what Iago’s part in all this may be, Othello has committed a crime for which there can be no forgiveness. Othello himself knows this, and does not look for absolution, either in this world, or in the next: he knows at the end that he is irrevocably damned, and that Desdemona, his vision of heaven, is lost to him for all eternity. At the end, he asks someone to ask Iago why “he hath ensnared my soul”. Iago refuses to answer: “what you know, you know,” he says. And given what Othello knows, he cannot even hope for redemption of his soul:

When we shall meet at compt,

This look of thine will hurl my soul from heaven,

And fiends will snatch at it. Cold, cold, my girl!

Even like thy chastity. O cursed slave!

Whip me, ye devils,

From the possession of this heavenly sight!

Blow me about in winds! roast me in sulphur!

Wash me in steep-down gulfs of liquid fire!

O Desdemona! Desdemona! dead!

This look of thine will hurl my soul from heaven,

And fiends will snatch at it. Cold, cold, my girl!

Even like thy chastity. O cursed slave!

Whip me, ye devils,

From the possession of this heavenly sight!

Blow me about in winds! roast me in sulphur!

Wash me in steep-down gulfs of liquid fire!

O Desdemona! Desdemona! dead!

Of course, one may say that Iago made him do it. I doubt whether that would count as much of a mitigating factor in court, but to understand the drama, we must try to understand the nature of both Iago and of Othello.

Iago is a fascinating character, but also, I think, a very shallow character. There are some who think that it is actually Iago, and not Othello, who is at the centre of the play. I find myself disagreeing with this strongly. It is true that Iago is on stage longer than Othello, and has more lines; but Iago is, I think, incapable of feeling anything very deeply. For instance, consider his suspicion of Emilia: he tells us, twice, that he suspects his wife of having had an affair with Othello (for which, incidentally, Shakespeare gives us not a shred of evidence), and he says that the thought of this “gnaws [his] inwards like a poisonous mineral”. But he only says this: we don’t see him feeling anything- certainly nothing remotely comparable to the inner torment Othello later feels when he begins to suspect his wife. Iago, I think, wanted Othello merely to experience something of thediscomfort he had himself experienced; but when Othello reacts with far greater passion (in III,iii, 362ff), Iago is taken by surprise: the depth and intensity of Othello’s passion are beyond Iago’s own narrow emotional horizons.

There is a very surprising scene also in IV,ii, where Iago is made to witness Desdemona’s distress. And here, too, I think Iago is taken by surprise. He says a few comforting words to Desdemona, but on the whole, seems surprisingly ill at ease: it’s one of the few scenes in the play where he is not in charge of the proceedings. Immediately afterwards, Iago meets with Roderigo, and in this confrontation, it is Roderigo who does most of the talking, and the normally loquacious Iago is mainly restricted to the occasional “go to” and “very well”. I think the reason for this is that Iago has been affected by Desdemona’s distress: his own limited imaginative capability could not have foreseen the depths of Desdemona’s anguish – it is well beyond his own stunted emotional range.

The eternal question, of course, is that of motive: why does Iago do all this? Iago himself gives two motives – that he had suspected Emilia with Othello, and that he had been overlooked for promotion. It has been said that neither motive is strong enough, but I don’t think that’s entirely true: it seems to me more the case that Iago does not appear to feel either motive very strongly. (And the very fact that he is given two motives when one would have been sufficient seems to me to weaken their power rather than otherwise.) Sure, he mentions these two motives, but when he does so, he seems curiously lacking in passion. Rather than seeking revenge for slights, real or imagined, it seems more likely that Iago is using these two reasons to spur himself on: this brings us to Coleridge’s famous formulation of “motiveless malignity searching for a motive”. But how does such malignity arise?

We get a clue, I think, in a revealing aside Iago has in V,i, where he speaks of Cassio having a “daily beauty in his life that makes me ugly”. Iago is aware that there is something missing in himself: what that something is, he does not know, but he knows that others have it, and that he doesn’t. He is a shallow character aware of his own shallowness. And in Othello and Desdemona, he seems to catch a glimpse of something that he knows is beyond his own narrow emotional horizons; and, although he cannot understand what exactly it is, he resents it.

Iago clearly did not intend everything from the very start: in his soliloquies, we see him making up the plan as he is going along, and, to begin with, he thinks of nothing further than placing impediments to Othello’s happiness. However, when Othello reacts with such unexpected passion, Iago realises that he has to go further – if only for his own safety (Othello threatens to kill him if he doesn’t provide proof of Desdemona’s infidelity); and as he does so, he finds himself enjoying the power he now wields over Othello, who is his superior in every way – in both social and military hierarchies, and also morally and spiritually. Iago finds enjoyment in his ability to bring Othello down to his own level: it is tremedously exciting. And, intoxicated by this sense of excitement, he goes further and further, unable to resist.

Yes, Iago is a fascinating character, but it is Othello who is at the centre of the play. Iago is at the end what he had been at the start – a morally and emotionally stunted character: it is in Othello that we see a nobility of soul, a grandeur that makes his descent into damnation all the more painful. And in the innocent, childlike Desdemona, we are offered an antithesis to Iago. “We work by wit, and not by witchcraft,” Iago says near the start of the play; Desdemona, on the other hand, works by witchcraft – of a sort: indeed, her lord father had suspected sorcery in her love for Othello, and in a sense, he was right, but it is not the sort of enchantment he had in mind. So, at the end, Iago, still alive, refuses to speak further, while in contrast, Desdemona speaks miraculously from apparently beyond death to forgive Othello: where Iago ensnares Othello’s soul, Desdemona offers the possibility of redemption – a redemption that, by the end, Othello does not himself look for.

There is a mystery at the heart of the relationship between Othello and Desdemona. On the surface, this is a story of a European woman who unwisely marries someone from a background very different from her own, and eventually pays for her mistake with her life as she becomes the victim of an honour killing. But if we see the play in these terms (and rather depressingly, many do – even certain “cultural commentators” who write for national newspapers!), we miss the essence of this very profound work.

I think that to appreciate the nature of the drama, we must consider the nature of the relationship between Othello and Desdemona. In I,iii, Desdemona’s lord father, upon taking his leave of her, says to Othello: “She has deceived her father, and may thee.” Othello’s reply is magnificent: “My life upon her faith.” This is no mere figure of speech: Othello really has staked his very life on the matter. Desdemona is his image of heaven itself, and if this image proves false, then the all of life itself becomes insignificant, devoid of meaning. This is made quite clear by the imagery of heaven and hell, and of salvation and damnation, that runs throughout the play:

Perdition catch my soul,

But I do love thee! And when I love thee not

Chaos is come again.

(III,ii,90-92)

But I do love thee! And when I love thee not

Chaos is come again.

(III,ii,90-92)

If she be false, O then heaven mocks itself,

I’ll not believe it.(II,iii,283-4)

I’ll not believe it.(II,iii,283-4)

But there where I have garnered up my heart,

Where I must live or bear no life,

The fountain from which my current runs

Or else dries up –(IV,ii,58-61)

Where I must live or bear no life,

The fountain from which my current runs

Or else dries up –(IV,ii,58-61)

Such depth of feeling, such witchcraft, is beyond the scope of Iago’s wit. But Iago’s perspective is, of course, a very limited one. He cannot see the extent to which Othello has invested his very being into his love for Desdemona. This is, indeed, beautiful and noble, but it is also dangerously fragile; and Iago, being what he is, cannot understand the beauty and the nobility, but he does detect its fragility,

It is fragile because Othello and Desdemona come from completely different worlds. It is not merely a question of race (although it seems that modern interpretations of this play seem fixated on the issue of race at the cost of everything else): Othello is, for a start, much older than Desdemona; and on top of that, he comes from a different culture, a different world. Othello has no understanding of the world of the aristocracy, any more than Desdemona has any understanding of the world of military campaigns. Their decision to marry was a tremendous act of trust and of faith on both sides. Such trust is, of course, very beautiful, but once it is broken, there remains no stable base. Othello himself knows this: he has, as he says, “garnered up” his very heart in Desdemona’s love, and it is from there that his “current runs, or else dries up”: there is no middle course.

But once Iago breaks this fragile trust, Othello’s mind itself collapses. The exact nature of this fragility depends upon the interpretation: Antony Hopkins, in the BBC production, played up the fragility – he was, throughout, insecure in his relationship with Desdemona. Willard White, in Trevor Nunn’s RSC production (also available on DVD) takes Othello at his word: his Othello is not “easily jealous”, but, “being wrought, perplexed in the extreme”. But however we interpret this, the blind trust between Othello and Desdemona is fragile indeed, and no-one knows this better than Iago.

Iago knows that the world of the aristocracy is a closed book to Othello, who knows nothing about its customs and mores, about how people behave in that society. What Othello does know – and hence trusts – is the world of the military. Soldiers have to rely on each other implicitly: often, they rely on each other for their very lives. So when a fellow soldier – especially someone as universally renowned for his honesty as Iago is – suggests something, it is very powerful. And it is all the more so when that suggestion concerns something that Othello knows he does not understand – i.e. aristocracy. Even so, Othello resists: after Iago first starts to apply his poison, Othello says “If she be false, heaven mocks itself: I’ll not believe it”. But for the drama to work, we must appreciate how very potent this particular poison is: quite literally, it drives Othello mad. He turns on Iago with a violent fury, threatening to kill him:

Villain, be sure thou prove my love a whore,

Be sure of it, give me ocular proof,

Or by the worth of man’s eternal soul

Thou hadst better been born a dog

Than answer my wak’d wrath!

….

If thou dost slander her and torture me

Never pray more, abandon all remorse;

On horror’s head horrors accumulate,

Do deeds to make heaven weep, all earth amazed,

For nothing canst thou to damnation add

Greater than that!

(III,iii,362-376)

Be sure of it, give me ocular proof,

Or by the worth of man’s eternal soul

Thou hadst better been born a dog

Than answer my wak’d wrath!

….

If thou dost slander her and torture me

Never pray more, abandon all remorse;

On horror’s head horrors accumulate,

Do deeds to make heaven weep, all earth amazed,

For nothing canst thou to damnation add

Greater than that!

(III,iii,362-376)

(Once again, “eternal soul”, “heaven” and “damnation”! But whose damnation is Othello referring to? Iago’s, or his own?)

This is way beyond Iago’s understanding. But he knows that he can’t now stop here. And Othello, who has always been aware of the fragile nature of his faith in Desdemona, is now easy prey in Iago’s hands.

The final scene of this play is gut-wrenching. Othello knows he is damned: he does not ask for pardon or for mercy, either in this world or in the next. He knows the earth-shattering nature of the crime he has committed, and nothing can he to damnation add greater than that.

All Shakespeare’s tragic protagonists undergo a transformation, but none undergoes a transformation more dramatic than does Othello, who changes from a man of noble character and of spiritual grandeur into an unhinged wife-killer, a child-killer. He comes down, indeed, to the level of Iago, and one cannot descend to a level lower than that. (Othello’s unspeakably horrible murder of Desdemona has been pre-figured in the earlier scene by Iago’s murder of Roderigo, who, like Desdemona, is also, I think, a teenager.)

Desdemona doesn’t have as prominent a part in the play as does Othello and Iago. While Shakespeare was happy to write leading parts for women in his comedies (Rosalind, Viola, Beatrice, etc.), he seemed less keen to write prominent parts for women in tragedies: this may have been because he didn’t feel that the boy actors available for female roles could convincingly depict tragic passion – although, presumably, he changed his mind on that score by the time he came to create Lady Macbeth and Cleopatra. But whatever the reason, Desdemona is not as much at the forefront of the drama as are Othello and Iago. But that is not to say that she is not characterised.

If it is true that Desdemona has an idealised vision of Othello, it is also true that Othello has an idealised view of Desdemona: to Othello, Desdemona is a vision of heaven itself. But Shakespeare presents both as real characters, and not as ideals. Desdemona eventually does prove herself to be something of a saint, but this is all the more moving because she has been depicted not in terms of an ideal, but as a figure of flesh and blood. Far from being some sort of perfect vision, she is a young woman capable of deceiving her own lord father and the society she came from: this, indeed, is one of the main planks of Iago’s case – “This girl deceived her own lord father, the only family she had, aside from all of high society; and is therefore, is not only capable of deceiving, but is well-versed in the art of deception.” Othello cannot deny this, and neither can we, the audience.

Another point is the lie she tells Othello. When he asks her if the handkerchief is lost, she instantly answers it isn’t, even though, earlier in the scene, she had asked Emilia where she thinks she may have lost it. This seems to me the instinctive reaction of a child afraid of being told off. As to the question of why she hadn’t looked after the thing properly, well – she’s an aristocrat, and is used to having servants picking things up after her.

There’s also the scene where she pleads for Cassio to be reinstated. Now, Cassio has been quite rightly demoted for having been drunk while on guard duty. Whatever Iago’s part in the incident, for a senior officer such as Cassio to become drunk while on duty (especially in a time of war) is an extremely serious matter, and one suspects that were it not for Othello’s personal regard for him, Cassio may well have been clapped in irons and court-martialled. Desdemona is completely out of order in interfering in such a case, and pleading on Cassio’s behalf. Othello, as a military leader, must realise how improper it would be to reinstate Cassio, and he should have asked Desdemona, gently but firmly, not to interfere in this matter; but he seems incapable of doing so, and merely puts the thing off, saying to her “I will deny thee nothing”. (Antony Hopkins is particularly good in this scene in the BBC production: he seems unable to look Desdemona in the eye here, and started fidgeting with various things.) We may wonder why Othello behaves this way, but the reason for Desdemona’s behaviour isn’t hard to deduce: she is still childlike and immature, and, what’s more, she is still the spoilt daughter of privilege, an only child used to being pampered by her indulgent lord father, and blissfully unaware of the wider issues in the big bad wide world. In short, given her social background and her upbringing, Desdemona is, throughout, a perfectly believable creature of flesh and blood.

And, although Desdemona is usually played by a mature actress, I really cannot see her as anything other than a child, or at least an adolescent. There is much that is child-like about her behaviour. Emilia, for instance, says of her:

…but she so loves the token [the handkerchief],

For he conjured her she should ever keep it,

That she reserves it evermore about her

To kiss and talk to.

For he conjured her she should ever keep it,

That she reserves it evermore about her

To kiss and talk to.

This is very much the behaviour of a child. Her failure to see that mention of Cassio is driving her husband mad seems to me very odd in a mature adult, but in a child inexperienced of life, it is more understandable. And her pleading on behalf of Cassio, while inexcusable in a mature woman in mid-adulthood, is perfectly understandable in a child used to asking for favours. And she seems to look on Emilia almost as a sort of mother-figure (or aunt figure, or oneesama), although Emilia herself, married to a man who says he is twenty-eight years old, is most likely still in her twenties.

All of this makes it all the more surprising that this otherwise unremarkable girl, still virtually a child, should make such an extraordinary leap of faith to marry Othello: there is, indeed, some form of witchcraft in this. She breaks off completely from the only society she knows, and goes off to a completely alien environment – a military outpost on the front line of a war. However, if Othello and Desdemona had seen each other in terms of ideals, neither is really greatly mistaken: for Othello is the great hero that Desdemona sees in him; he is a man of real nobility, and of moral and spiritual grandeur: were it not so, his moral decline would have been, in dramatic terms, unremarkable. Othello is a man who feels deeply, a man who loves not wisely, but too well. And, as the play progresses, it becomes apparent that Desdemona, for all her immaturity and her foibles, is also a saint: when Othello saw in her a vision of heaven, he wasn’t far mistaken. But Shakespeare depicts this saint very much as a creature of flesh-and-blood. It may be said with some justification that in King Lear, Cordelia is more important for what she represents than for what she is, but I don’t think this can be said of Desdemona, who emerges as a well-rounded, well-characterised figure in the drama. And it is precisely because she is so believable that her tragedy, and her forgiveness, are so unbearably moving.

Iago may be the epitome of evil and Desdemona the epitome of saintliness, but Shakespeare saw both in human terms. And, despite delving into these characters as deeply as he could – or as deeply as anyone could – he acknowledges the mystery that lies at their heart, the mystery that lies at the heart of human existence itself.

***

The structure and pacing of the play are also deserving of comment. Given how tense the tragedy is, the tempo at the start is surprisingly leisurely. For almost half the play – right up to the middle of the third act – Shakespeare maintains this leisurely tempo. It’s not that nothing happens – far from it: but there seems little sense of urgency. But it is in Act 3 scene 3 (a worthy contender for the single greatest scene that Shakespeare ever wrote) that it really starts to grip. Indeed, in this scene, we find ourselves caught in a vice: it is here that Iago first starts applying the poison to Othello’s mind. And from this scene onwards, Shakespeare does not let up. In terms of emotional involvement, I don’t think any other play in the canon can quite compare with this. We register every agony felt by Othello and by Desdemona: no matter how often I revisit the play, I seem to re-live this extraordinary intensity of mental turmoil. If Othello’s mind becomes unhinged – as it surely does – we can feel why it does so, even if we cannot explain it fully to our satisfaction.

Perhaps we can never explain it. Great works of art always retain that mystery at their heart – although that is not to say we shouldn’t try to think about it as deeply as we can. Certainly, not even Shakespeare ever wrote anything more wonderful than this.

Some Further Thoughts on Emilia and Iago (and Cassio as well)

The problem with trying to write about something such as Othello is that even after you’ve written thousands of words, you still feel you’ve barely scratched the surface. It feels like probing an iceberg - how large is that iceberg, how deep into the ocean is the plunge?

The problem with trying to write about something such as Othello is that even after you’ve written thousands of words, you still feel you’ve barely scratched the surface. It feels like probing an iceberg - how large is that iceberg, how deep into the ocean is the plunge?

One question is often raised about Emilia: how much did she know of her husband’s plotting? I personallty don’t think that she did know about it. When Othello, after killing Desdemona, mentions that it was Iago who had told him about Desdemona’s unfaithfulness, there can be no doubting Emilia’s surprise and shock:

OTHELLO

Cassio did top her; ask thy husband else.

O, I were damn’d beneath all depth in hell,

But that I did proceed upon just grounds

To this extremity. Thy husband knew it all.

Cassio did top her; ask thy husband else.

O, I were damn’d beneath all depth in hell,

But that I did proceed upon just grounds

To this extremity. Thy husband knew it all.

EMILIA

My husband!

My husband!

OTHELLO

Thy husband.

Thy husband.

EMILIA

That she was false to wedlock?

That she was false to wedlock?

OTHELLO

Ay, with Cassio. Nay, had she been true,

If heaven would make me such another world

Of one entire and Perfect chrysolite,

I’ld not have sold her for it.

Ay, with Cassio. Nay, had she been true,

If heaven would make me such another world

Of one entire and Perfect chrysolite,

I’ld not have sold her for it.

EMILIA

My husband!

My husband!

OTHELLO

Ay, ’twas he that told me first:

An honest man he is, and hates the slime

That sticks on filthy deeds.

Ay, ’twas he that told me first:

An honest man he is, and hates the slime

That sticks on filthy deeds.

EMILIA

My husband!

My husband!

OTHELLO

What needs this iteration, woman? I say thy husband.

What needs this iteration, woman? I say thy husband.

A bit later, when Iago enters, we get this:

EMILIA

O, are you come, Iago? you have done well,

That men must lay their murders on your neck.

O, are you come, Iago? you have done well,

That men must lay their murders on your neck.

GRATIANO

What is the matter?

What is the matter?

EMILIA

Disprove this villain, if thou be’st a man:

He says thou told’st him that his wife was false:

I know thou didst not, thou’rt not such a villain

Disprove this villain, if thou be’st a man:

He says thou told’st him that his wife was false:

I know thou didst not, thou’rt not such a villain

This does not seem like counterfeiting to me. Emilia is certain that her husband, whatever faults he may have had, could not be such a villain. A bit villainish, may be – but not such a villain.

Yes, it is true that Emilia had picked up the handkerchief when Desdemona had dropped it, and had given it to Iago, as he had requested. She is not entirely unquestioning: she does ask “why?”; but she does not insist on an answer to her question:

EMILIA

What will you do with ‘t, that you have been

so earnest

To have me filch it?

What will you do with ‘t, that you have been

so earnest

To have me filch it?

IAGO

[Snatching it] Why, what’s that to you?

[Snatching it] Why, what’s that to you?

EMILIA

If it be not for some purpose of import,

Give’t me again: poor lady, she’ll run mad

When she shall lack it.

If it be not for some purpose of import,

Give’t me again: poor lady, she’ll run mad

When she shall lack it.

IAGO

Be not acknown on ‘t; I have use for it.I

Go, leave me.

Be not acknown on ‘t; I have use for it.I

Go, leave me.

She clearly does not know what Iago plans to do with the handkerchief. This brief scene between Emilia and Iago does suggest very strongly to me that their marriage is on the rocks. Iago, we know, suspects Emilia of being unfaithful (although there is no evidence apparent for this). And when later in the play, Emilia speaks passionately of the bad treatment wives get from their husbands, one feels that she may be speaking from experience:

But I do think it is their husbands’ faults

If wives do fall: say that they slack their duties,

And pour our treasures into foreign laps,

Or else break out in peevish jealousies,

Throwing restraint upon us; or say they strike us,

Or scant our former having in despite;

Why, we have galls, and though we have some grace,

Yet have we some revenge. Let husbands know

Their wives have sense like them: they see and smell

And have their palates both for sweet and sour,

As husbands have. What is it that they do

When they change us for others? Is it sport?

I think it is: and doth affection breed it?

I think it doth: is’t frailty that thus errs?

It is so too: and have not we affections,

Desires for sport, and frailty, as men have?

Then let them use us well: else let them know,

The ills we do, their ills instruct us so.

If wives do fall: say that they slack their duties,

And pour our treasures into foreign laps,

Or else break out in peevish jealousies,

Throwing restraint upon us; or say they strike us,

Or scant our former having in despite;

Why, we have galls, and though we have some grace,

Yet have we some revenge. Let husbands know

Their wives have sense like them: they see and smell

And have their palates both for sweet and sour,

As husbands have. What is it that they do

When they change us for others? Is it sport?

I think it is: and doth affection breed it?

I think it doth: is’t frailty that thus errs?

It is so too: and have not we affections,

Desires for sport, and frailty, as men have?

Then let them use us well: else let them know,

The ills we do, their ills instruct us so.

It may be possible, I think, that Emilia gives the handkerchief to her husband as a sort of peace offering. Of course, she sees (in III,iv) that Othello is angry with Desdemona for having lost the handkerchief, but, not knowing how Iago has been affecting Othello’s mind, she is in no position to judge the severity of this matter: as far as she can see, it is simply a domestic row – the sort of thing that may be quite commonplace in her own life. Of course, she could have said that the handkerchief was with Iago, but she could not do this without giving her husband away. As far as she is concerned, nicking the handkerchief was just a piece of petty pilfering and nothing more, and she certainly wasn’t going to incriminate her husband on that point just to settle a domestic row between Othello and Desdemona.

Of course, things get much worse after that, as Othello strikes Desdemona in public (IV,i), and then humiliates her horribly in a scene that is almost too unbearable even to read (IV,ii), but there is no reason for Emilia to associate any of that with the handkerchief.

Does she suspect Iago? I doubt it. In IV,ii, after that terrible scene between Othello and Desdemona, Emilia vents her fury at the injustice of it all; but, interestingly, the fury is aimed not at Othello, but at someone who Emilia imagines (as it happens, quite rightly) has been poisoning Othello’s mind. Although she comes very close to the truth in her guessing, I’d be very surprised if she suspected her own husband as the villain. If she did, her words to him at the end would make little sense:

Disprove this villain, if thou be’st a man:

He says thou told’st him that his wife was false:

I know thou didst not, thou’rt not such a villain

He says thou told’st him that his wife was false:

I know thou didst not, thou’rt not such a villain

I really can’t see any evidence in any of this to suggest that Emilia suspected her husband, even vaguely. If she had done, and had remained silent, then she would have been complicit in the terrible crime. And yet, her distress on discovering the crime can hardly be doubted. When she realises the truth, she insists on speaking it. Given the social mores of the time, the wife was expected to obey the husband (which is, indeed, what Emilia had done when she pilfered the handkerchief for him); but now, to reveal the truth, she is prepared to defy those social mores:

IAGO

What, are you mad? I charge you, get you home.

What, are you mad? I charge you, get you home.

EMILIA

Good gentlemen, let me have leave to speak:

‘Tis proper I obey him, but not now.

Perchance, Iago, I will ne’er go home.

Good gentlemen, let me have leave to speak:

‘Tis proper I obey him, but not now.

Perchance, Iago, I will ne’er go home.

She even has a premonition of her own end at this point, I think, when she speaks those last words.

Emilia, in this scene, is heroic. Whatever petty pilfering she may have done in the past, she is now prepared to sacrifice her very life to reveal the truth about her beloved Desdemona. A few minutes earlier, she had said this to Othello:

Thou hast not half that power to do me harm

As I have to be hurt.

As I have to be hurt.

This is magnificent. Emilia feels that the willingness to receive hurt for the sake of the truth is in itself a strength. As, indeed, it is. This moral strength that she displays, the power of her love for the dead Desdemona, is something else that was beyond Iago’s limited horizons: he could only see into the weaknesses of people, but such matters as moral courage or self-sacrifice are beyond his limited vision. Just as he could not even conceive the nature of the relationship between Othello and Desdemona, neither could he conceive that Emilia – whom he had taken for granted – would be prepared even to face death for the sake of someone she had loved. The more I ponder this, the more I think how very pathetic and lacking in insight Iago’s view of humanity really is: the worst he can see in people is the only truth there is for him. Although he succeeds in bringing Othello down to his level, humanity is capable of being far, far greater than Iago could ever imagine.

Othello, it is true, does not see through Iago, but neither does anyone else. He is referred to throughout by everyone as “honest”. In Act One, Othello proposes that Iago escort Desdemona to Cyprus, saying about him: “A man he is of honest and trust.” If anyone had known Iago to have been otherwise, they would have objected immediately, but no-one does. Later, we see that Iago is trusted by Cassio, who is happy to take his advice on being re-instated. Desdemona, when in deep distress in IV,ii, asks Emilia to fetch her husband to advise her. And after Cassio is wounded and Roderigo murdered, both Ludovico and Gratiano trust Iago, and are happy to allow him to take charge of matters:

GRATIANO

This is Othello’s ancient, as I take it.

This is Othello’s ancient, as I take it.

LUDOVICO

The same indeed; a very valiant fellow.

The same indeed; a very valiant fellow.

I think Iago was overlooked for promotion because of his class. He is actually quite right when he says this:

Why, there’s no remedy; ’tis the curse of service,

Preferment goes by letter and affection,

And not by old gradation, where each second

Stood heir to the first.

Preferment goes by letter and affection,

And not by old gradation, where each second

Stood heir to the first.

My history books tell me that Cromwell’s New Model Army was successful in part because it was a complete meritocracy: promotion depended purely on ability, not on social standing. And Shakespeare, of course, predated the New Model Army (and eighteenth-century military academy). Cassio is an aristocrat: he belongs to the same social circles as Desdemona. In II,1, while they are all waiting anxiously for Othello’s ship to arrive, Desdemona whiles away the time for a bit listening to Iago’s jokes, but then goes off with Cassio to one side of the stage to speak in private – away from the mere “riff-raff”, as it were. Iago notices this, and resents this. Cassio seems to me a sort of Renaissance equivalent of the Sandhurst-trained officer: Harrow, Cambridge, Sandhurst… he has all the connections, and, naturally, gets the top posts. At no time does he show any leadership qualities: indeed, when he gets drunk while on guard duty, he displays qualities that should have disqualified him from high position altogether. And yet, even so disgraceful a display earns him a mere demotion rather than a court-martial; and later, he is appointed the new Governor of Cyprus. Iago is well within his rights to resent this.

But for all this, I don’t think it is this motive (any more than the belief that his wife had slept with Othello) that drives him on: he doesn’t seem to feel any of this strongly enough. He seems to use these motives merely to spur himself on into doing what he wants to do anyway. For instance, when he speaks of his suspicion that Emila has had an affair with Othello:

And it is thought abroad, that ‘twixt my sheets

He has done my office: I know not if’t be true;

But I, for mere suspicion in that kind,

Will do as if for surety.

He has done my office: I know not if’t be true;

But I, for mere suspicion in that kind,

Will do as if for surety.

In short, “I don’t know if this is true, but I’ll assume it is, and go on from there.” This seems strange. If the thought bothers him, why not investigate it further? Why not look for evidence one way or the other? And similarly with being overlooked promotion: if it really rankles with him, why does he mention it so rarely? Surely, if this were a major motive, it would always have been in the forefront of his mind? And if it was, then surely – given his extreme loquacity – he’d have mentioned it more often? But he mentions it only once, and then seems to forget all about it. He may feel these things – but he really he doesn’t seem to feel them strongly enough. Certainly not strongly enough to justify the atrocities he commits: one has to feel very strongly indeed to do something so unspeakable.

No matter how much one writes about these characters, one still feels that one hasn’t scratched the surface. And I’m sure that the next time I read or see this play, I’ll think about it differently once again…

“Chaos is come again”: “Othello” at Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-on-Avon

The following is a not really a review – I don’t really do reviews, as such! – it’s more an attempt to make sense of various thoughts that struck me on seeing The Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of Shakespeare’s Othello from the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-on-Avon, directed by Iqbal Khan. I saw it as a live cinema broadcast on August 26th, 2015.

Not being a very frequent theatre-goer, I cannot claim to be in any way an authority on interpretations of Shakespeare’s plays in performance, and of how these interpretations have changed over time, but I do get the distinct impression that depictions both of Othello the play, and of Othello the character, have changed quite significantly: they have both become much harsher than they used to be. Not that interpretations used to be all sweetness and light: that is hardly possible in a play in which the titular character ends up murdering his innocent and helpless wife onstage; but actors and directors are, it seems to me, less inclined nowadays to portray Othello as an essentially noble figure. Some forty or fifty years ago, judging by the audio recordings that still survive from that era, and remembering also what I can of a wonderful performance I had attended in the Royal Shakespeare Theatre back in 1979 (with Donald Sinden a quite magnificent Othello), performances emphasised a certain nobility, a certain majesty, in Othello’s character: indeed, it was because he was so grand and so noble a figure that his transformation into a murderous beast seemed so particularly horrible. Actors found in his lines a solemnity and grandeur that, even at the height of his homicidal rage, seemed to foreshadow the sublimity and magnificence of Milton:

Never, Iago: Like to the Pontic sea,

Whose icy current and compulsive course

Ne’er feels retiring ebb, but keeps due on

To the Propontic and the Hellespont,

Even so my bloody thoughts, with violent pace,

Shall ne’er look back, ne’er ebb to humble love,

Till that a capable and wide revenge

Swallow them up.

But more recent Othellos tend to eschew this kind of approach: instead of the sonorous grandeur that actors of a previous generation had found, modern Othellos tend to break these lines up into shorter units, preferring staccato rhythms to long legato lines. The effect is to diminish, or even to deny altogether, the sense of nobility in the character. I suppose this reflects in part a modern sensibility that is sceptical of the very idea of nobility or of sweetness: actors do not generally depict Hamlet as a “sweet prince” either these days. But I wonder to what extent this harsher, and, some would say, less sentimental view of Othello – both of character and of play – is informed by the well-known 1952 essay by F. R. Leavis, “Diabolic Intellect and the Noble Hero” (included in this collection), in which it is argued with considerable vigour that Othello, far from being the noble and dignified protagonist that A. C. Bradley had described in his famous study, is actually a most ignoble and, indeed, shallow personage, vain and self-dramatising, unworthy of Desdemona, and unable, given his shortness of vision and triviality of mind, even to come close to appreciating her worth.

Bradley is very much Leavis’ target in this essay, and in every way, Leavis seems Bradley’s opposite: where Bradley is gentlemanly and charming, Leavis is abrasive, relishing a trenchant and quite wicked vituperative wit. And where Bradley tries to find the best he can in the characters, Leavis only sees characters who are morally short-sighted, blinkered, self-serving, and most ignoble.

There are two main points in which Leavis takes issue with Bradley: firstly, he rubbishes Bradley’s contention that it is really Iago who is at the centre of the play; and secondly, he rips to shreds – with some gusto – the idea that Othello possesses even the slightest hint of nobility or of dignity. On the first point, I agree with Leavis whole-heartedly: Iago certainly has more lines than Othello, but this hollow, pathetic shell of a man, lacking as he does anything of Macbeth’s pained consciousness of the damnation of his soul – lacking consciousness even of the existence of a soul that may be damned – simply does not have enough substance to hold the centre of so immense a tragic work. But Leavis’ second point – that Othello is similarly hollow – I find more troubling. If the drama is essentially that of an empty eggshell cracked open revealed its emptiness, then why does it grip so powerfully? Why is it that by the end of a reading, or of a good performance, we feel that we have glimpsed into the very depths of the human soul?

Leavis certainly does not see the play in such grand terms: at the end of his essay, he writes:

It is a marvellously sure and adroit piece of workmanship; though closely related to that judgement is the further one that, with all its brilliance and poignancy, it comes below Shakespeare’s supreme – his very greatest – works.

I couldn’t help feeling when I first read this essay that, given Leavis’ view of the character of Othello, his judgement on the play could not be otherwise – that the mere cracking open of an empty shell to display the emptiness is not and cannot be the stuff of supreme masterpieces. But since it does seem to me self-evidently a supreme masterpiece, it must surely follow that there are flaws in Leavis’ arguments. However, what is remarkable is that even when Othello is played as Leavis had seen him (Antony Hopkins’ interpretation in the 1981 BBC production strikes me as very Leavisite in conception), the drama retains still its extraordinary power. In other words, Leavis’ conclusion is not inevitable, even if we were to accept his arguments: Othello himself can be hollow and empty, lacking in nobility or in majesty, but the tragic power of the drama, even from this Leavisite perspective, somehow remains undiminished. And it is worth investigating where this tragic power lies: if it is not in the depiction of the great fall of a great man – since Othello is not great here to begin with – where is it?

My own view of the play – an interpretation that for many years has satisfied me, and which continues, despite Leavis, to satisfy – I tried to describe here, and there’s little point my repeating it; however, Leavis’ view is certainly worth considering, not merely because he was among the most perceptive of literary critics both of his or of any other generation, but also because his interpretation is coherent, and entirely consistent with Shakespeare’s text. But it does leave us with an enigma: a drama that, on the surface, should really be quite trivial – the exposure of a hollow man as but a hollow man – turns out to be gut-wrenchingly intense. How can this be?

This latest RSC production is Leavisite in many ways. Othello, played by Hugh Quarshie, is allowed little of the nobility and majesty that I remember from Donald Sinden’s performance of the late 70s, or is apparent in the thrilling performance by Richard Johnson in an audio recording from the 60s. This lack of nobility is clearly a conscious decision, since Quarshie, given his stage presence and charisma, his superb verse-speaking, and, not least, his imposing and sonorous voice, is certainly more than capable of depicting nobility had he so wanted. But this Othello is far from noble: we see him happy to oversee torture of prisoners as a routine part of his job; and, right from the start, he seems to express little sense of wonder that Desdemona had chosen him: he takes it all in his stride, as if all this were no more than his due. He is a supremely confident man, well aware that he can flout the authority even of a senator with impunity, and unsurprised that so valuable a prize as Desdemona – for prize is how he seems to consider her – could fall to him.

“Prize” is also the word Iago uses to describe Desdemona:

Faith, he to-night hath boarded a land carack:

If it prove lawful prize, he’s made for ever.

And in the next act, even as Othello expresses his love for Desdemona, he does so very disconcertingly in terms borrowed from the world of commerce, as if his union with Desdemona were no more than a financial contract:

Come, my dear love,

The purchase made, the fruits are to ensue;

That profit’s yet to come ‘tween me and you.

All this is in Shakespeare’s text: seeing Othello in such Leavisite terms is a valid interpretation of the text, and not an imposition. And, somewhat unexpectedly and very disconcertingly, it seems to point to certain parallels between Othello and Iago. These parallels are reinforced in this adaptation, as Iago here is also played by a black actor – Lucian Msamati. This casting removes – to a certain extent, at least – racism from Iago’s motivation, but what it substitutes in its place is most disturbing: for if it is true that Iago manages to bring down Othello to his own bestial level, the journey Othello makes is not a very long one; the implication seems inescapable that Othello, even from the start, is no stranger to Iago’s mindset.

Not that they are identical, of course: the differences are as important as the similarities. But the similarities are worthy of notice, for only when we are aware of these similarities do we realise the significance of the differences. Both Othello and Iago are aware, I think, that they are missing something in their lives – something vitally important. Iago, in a deeply significant aside, says of Cassio:

He hath a daily beauty in his life

That makes me ugly

And Othello, in parallel, knows that were he not to love Desdemona, his very soul would be lost, and his entire world collapse into chaos:

Excellent wretch! Perdition catch my soul,

But I do love thee! and when I love thee not,

Chaos is come again.

The use of the word “again” seems to imply that Othello is no stranger to “chaos”: for all his seeming confidence in the affairs of men, in other matters, he knows how precariously balanced his soul is between redemption and perdition.

But there, where I have garner’d up my heart,

Where either I must live, or bear no life;

The fountain from the which my current runs,

Or else dries up…

And here, I think, we see a very significant difference between the two – a difference that Leavis does not comment upon: where Iago wishes to destroy that quality which he knows he lacks – that “daily beauty” – Othello craves it, for he sees it as a path towards redemption. And this, I think, is what gives the play its gut-wrenching tragic power: even if Othello were to be everything Leavis claims he is, he seeks redemption: Iago doesn’t. Iago, working by “wit and not by witchcraft”, cannot bring himself even to believe in such a thing.

If I am on the right track on this, the tragedy lies not in Othello’s fall from a great height, but in his failure to reach that height in the first place. That height may be but vaguely glimpsed, but Othello, unlike Iago, is capable of glimpsing it, however vaguely, and the entire play seems suffused with a terror of that chaos that lies just under the surface of our lives – a chaos that prevents us from attaining those vaguely glimpsed heights, and which instead hurls our very souls from heaven.

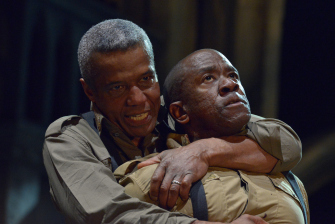

Hugh Quarshie as Othello and Lucian Msamati as Iago in “Othello”. Image courtesy Royal Shakespeare Company

This latest RSC production certainly captures that sense of terror. Othello as a play is curiously paced: the tempo seems quite slow for the first half, and, given that the play is most famous for its depiction of jealousy, Othello doesn’t even start to be jealous till after the half-way mark. But once it starts to grip – somewhere in the middle of Act 3, as Iago starts applying his poison – it doesn’t let go: even the “Willow song” scene, as Emilia prepares Desdemona for bed (IV,iii), where Shakespeare gives us something of a calm before the final storm, the air is thick with menace and with forebodings of impending doom. Perhaps no other play by Shakespeare, not even King Lear, leaves us quite so emotionally drained as does this.

It is Iago rather than Othello who commands centre stage for most of that first half, and Lucian Msamati gives a quite extraordinary performance here of a man who is, psychologically, deeply damaged. Some actors present Iago as a sort of likable villain, but Msamati’s Iago is, from the beginning, a dangerous sociopath. There is a powerful scene in the fourth act in which Desdemona, in her innocence and naivety, turns to Iago for help; and in this production, she kisses Iago in gratitude for what she thinks is his good advice. The sheer sense of physical revulsion with which Iago reacts to this kiss is startling. This is a man who finds the whole of humanity disgusting – he is obsessively cleaning up after everyone, as if the very physical presence of others is to him an abomination.

In the text, we clearly see Iago making up his plot as he is going along, and I have long thought that Iago engineers the destruction of Othello and of Desdemona only because, having underestimated the violence of Othello’s reaction, he is forced into doing so; but here, Iago wills the destruction from the start: it is merely the mechanism of his plot rather than its end that he has to improvise. Far from being a likable villain, this is an Iago whose very presence makes one’s skin crawl.

Quarshie’s Othello, as we first see him, is a man who is, seemingly, supremely confident. But Iago understands his weakness. He may not understand what Othello is aspiring towards, or why, but he is as aware as Othello is of the chaos that lies just below the surface, and he is aware of it because, in this, Othello resembles himself. And Othello’s surface cracks very quickly indeed. When Othello exits some half way through III,iii – the great scene in which Iago starts to apply his poison – he is perturbed, yes, but still in control of himself; but when he re-appears later in the scene, he is a raging maniac. This bipolar nature is, admittedly, written into the text itself, but I don’t think I’ve seen any actor emphasise this to the extent that Quarshie does.

Desdemona is one of Shakespeare’s most thankless roles. I think Shakespeare did depict a real flesh-and-blood woman rather than merely a symbol, but there seems little for the actress to do other than display vulnerability and bewilderment. By the end, of course, she proves herself saintly, as she miraculously forgives Othello seemingly from beyond death itself, but on the path to that ending there seems little scope for the actor playing Desdemona to make her mark. Joanna Vanderham does a fine job – at times going so far as to display resentment – but in terms of stage presence, Othello and Iago are too powerful to be easily removed from the centre. The “Willow song” scene – that calm before the storm that is nonetheless saturated with such deep foreboding – is particularly effective, with Ayesha Dharker a most effective Emilia.

Not that the production is beyond criticism. I regretted in particular the excision of Iago’s improvised cynical rhymes in II,i: presumably they were removed because they show Iago as too sociable a figure, but it would have been interesting to see how they might have fitted with Lucian Msamati’s interpretation. But the biggest misjudgement came, I think, in the later scene in which Cassio becomes drunk while on guard duty. Here. Iago’s song is replaced with a sort of karaoke scene, in which the soldiers improvise rhymes to each other. While most productions can get away with a bit of judicious cutting, it is never advisable to add lines to Shakespeare’s text, as the added lines are bound to suffer in comparison with what is around it. This is especially the case when the added lines are merely trivial doggerel, as they are here. Further, these lines indicate racial tensions amongst the soldiers, and there seems little point introducing such a theme in a play that gives no scope to develop it. The audience is simply left wondering what purpose this scene serves.

When, shortly afterwards, we see Othello supervising the torture of a prisoner, hooded and terrified, that seemed to me at first also to be a misjudgement – a fashionable reference to current world events that does little to advance the drama. But I was mistaken in this: this torture scene does actually fit into the overall concept of this production: such torture does take place in military bases, after all, and, since this Othello is not the majestic and noble figure that Bradley had envisaged, it is not amiss to see something of the brutal world with which he is so familiar. And in any case, torture is central to the play: Iago tortures Othello; Othello, in turn, tortures Desdemona (and, one may argue, himself); and at the end, once Iago’s villainies are exposed, Iago is threatened with actual physical torture. When Othello re-emerges in III,iii, raving like a maniac, he ties Iago to a chair that had previously been used for torture, and threatens to torture Iago physically even as Iago continues to torture him mentally: it is a scene of powerful theatricality. The only point that I’d take issue with is the appearance of Desdemona on stage even as the torture victim is still present. Now, given the conventions of the theatre, it is entirely possible for two people to be on stage together, and yet be in different places, so it is not necessarily the case that Desdemona sees the torture victim, or even that she is aware of the torture; but having them both on stage at the same time does inevitably implicate Desdemona in the torture, and that is surely a mistake.

So it’s not a flawless production by any means; but once it starts to exert its grip, it doesn’t falter. It demonstrates once again that a Leavisite view of Othello does not diminish the tragic greatness of the drama, but merely shifts its focus: the awe and the terror we experience are not occasioned by the fall of a Great Man, but springs, rather, from an awareness of the horror and of the chaos that lie immediately below the seemingly civilised surfaces of our human lives. However we view Othello, however we view its central character (who is most certainly Othello himself, and not Iago, as some still continue to insist), there is no other drama that is quite so gut-wrenching in its effect.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario